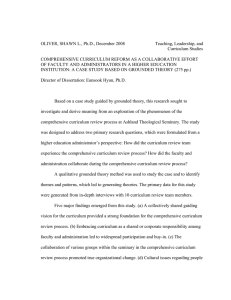

The Dissertation Committee for Timothy Dwight Lincoln certifies that

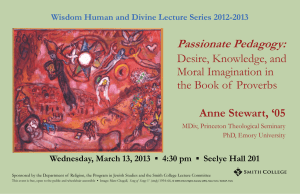

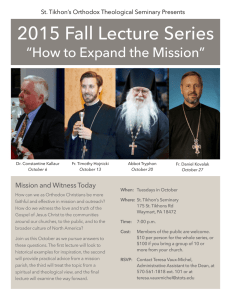

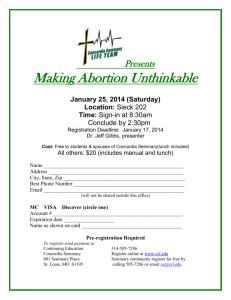

advertisement