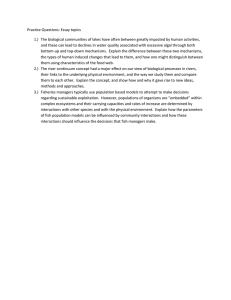

World Bank Document

advertisement