Community Outreach Partnership Center

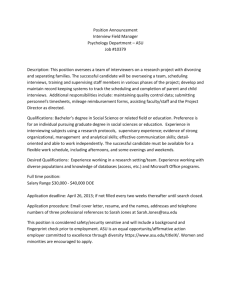

advertisement