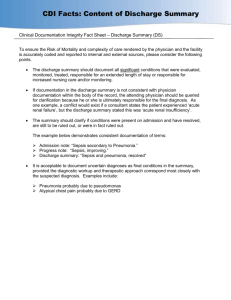

Discharge from hospital: pathway, process and

advertisement