Artificial Disks Replace Worn-Out Ones to Stop Back Pain from

advertisement

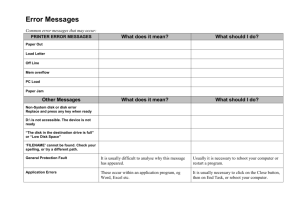

A Flexicore artificial disk, shown as it would be implanted between vertebrae. Artificial Disks Replace Worn-Out Ones to Stop Back Pain from Degenerative Disk Disease I f your knee or hip wears out, you can get it replaced. But if a disk in your spine degenerates, your only choice is the same one that existed nearly a century ago: have two adjacent vertebrae fused together. But soon, those in chronic pain from degenerative disk disease will have a better option: permanent replacement with an artificial disk. For the past two years, a team led by Thomas J. Errico, M.D., Associate Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery and Neurosurgery and Chief of the Spine Surgery Service at the Hospital for Joint Diseases (HJD), has been part of a clinical trial in which surgeons have replaced disks in the lower, or lumbar, spines of nearly 100 patients at HJD. Dr. Errico is now working on two new artificial disks, including one for the upper, or cervical, spine. A disk, the gel-like connective tissue between vertebrae, acts as a shock 6 NYU PHYSICIAN / Winter 2004–2005 absorber, rubber band, and ball joint all in one. It is the element that enables you to bend, flex, and stretch your back. But in degenerative disk disease, the spine undergoes a downhill cascade of events: Biochemical changes cause the disk to shrink, allowing the vertebrae to slip out of alignment, which can tear or rupture disks and pinch nerves. The result is excruciating back and leg pain. The current treatment for this often debilitating back condition is a procedure called spinal fusion. The worn-out disk is removed and a piece of bone is grafted between the vertebrae above and below it. In the new experimental procedure, instead of fusing the vertebrae, surgeons insert an artificial disk between them, a device made of two metal plates connected by a moving joint. Of the approximately half a million fusion patients in the U.S. each year, Dr. Errico estimates that a third of them could benefit more from disk replacement than fusion. The artificial disk allows the affected part of the spine to bend normally. When vertebrae are fused, they cannot move, which forces the rest of the spine to take up more of the burden of bending and flexing. As a result, as many as 30 percent of fusion patients will suffer degeneration of one or more additional disks within a decade after surgery. By maintaining movement in the affected area, artificial disks may prevent further degeneration. Several brands of artificial disks have been in clinical trials, and one received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in October 2004. Most of these artificial disks, including the FDA-approved model and the one that has been in trials at HJD, contain both metal and plastic parts. But plastic wears out over time, a fact that concerns some orthopaedic experts. Since most patients requiring disk replacement are relatively young, the ideal material is one that is more durable. Dr. Errico recently helped to develop a disk, called Flexicore, made entirely of a metal alloy called cobalt chrome. “That’s the material they use on the tips of bunker buster missiles,” says Dr. Errico. “We’ve tested Flexicore to the equivalent of 60 years of life, and there’s no visible wear.” The Flexicore disk is currently in two clinical trials—one in the U.S. at 22 institutions, and one in Europe. Dr. Errico is the principal investigator overseeing the U.S. trial. He is also helping to develop an artificial disk for the cervical spine. Called Cervicore, this new disk may undergo clinical trials beginning in early 2005. The artificial disk replacements have had encouraging early results. One of the Flexicore clinical trial patients is an avid figure skater who had been unable to do any advanced moves for several years because of lower back pain. “Three weeks after surgery,” says Dr. Errico, “she was out on the ice doing turns and spins.” ■ — By Fenella Saunders photography courtesy of stryker corp. news from medicine