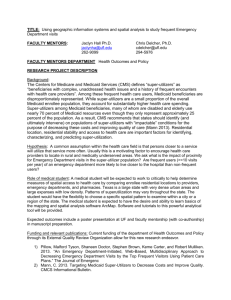

reduce costs - Center for Health Care Strategies

advertisement