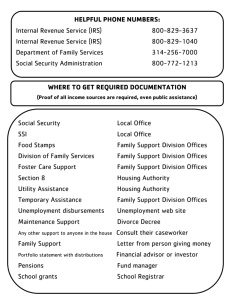

Head office location –

advertisement