PLAN SALT LAKE

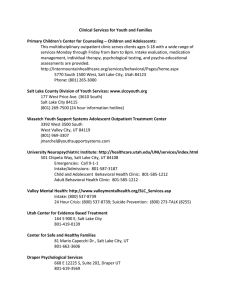

advertisement