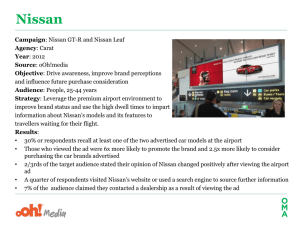

industry, Lessons from Nissan`s experience

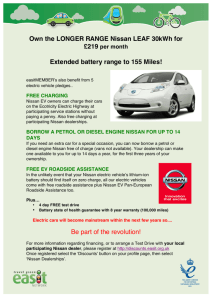

advertisement