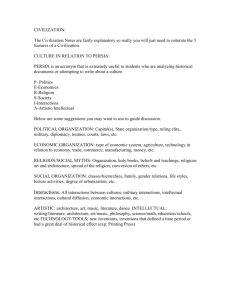

Improving knowledge transfer between research

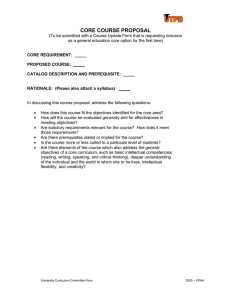

advertisement