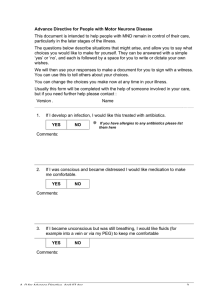

Liability for defective products

advertisement