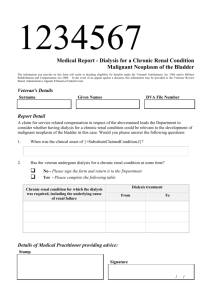

NSF Renal Services Part One: Dialysis and Transplantation

advertisement