here - Sheppard Mullin

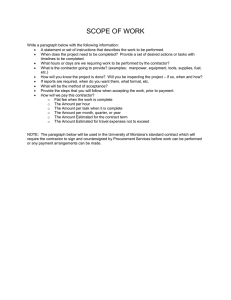

advertisement