cece v. holder - Emory University School of Law

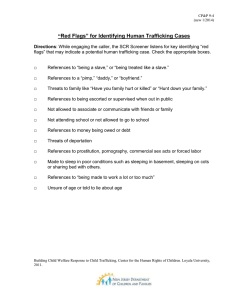

advertisement