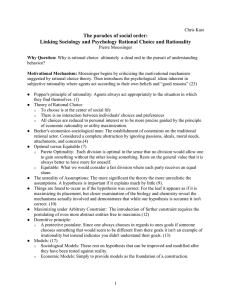

On Thoughtless Rationality (Rules-of -Thumb)

advertisement

KTKLOS, Vol. 40 -1987 -Fasc. 4,496-514

On Thoughtless Rationality (Rules-of -Thumb)

AMITAI ETZIO~I*

I.. THE ROLE OF RULES

In strenuous efforts to shore up the beleagueredneoclassic~lparadigm,

its followers argue that individuals may render rational decisions without processinginformation or deliberations, by using 'rules of thumb'.

'Cognitive capacity is a scarce resource like any other... To gather the information and

do the calculations implicit in naive descriptions of the rational choice model would

consume more time and energy than anyone has... Anyone who tried to make

fully-informed, rational choices would make only a handful of decisions each week,

leaving hundreds of important matters unattended. With this difficulty in mind, most

of us rely on habits and rules of thumb for routine decisions' [FRANK,1987,pp. 3-4].

These rules are provided to individuals by their culture, organizations, or are products of their previous experience.The 'discovery' of the

rules of thumb is tied to admission of information costsinto the neoclassical paradigm. Early neoclassical economic models assumed that all

individuals have perfect information, instantaneously and freely. Once

information costs were included, it became evident that many optimal

calculations are too costly to complete. As BAUMOL

and QUANDT[1964,

p. 23] put it:

'the morerefinedthe decisionmaking process,the moreexpensiveit is likely to be,and

therefore,especiallywherea decisionis not of crucial importance,no more than an

approximate solution may be justified. Since all real decisions are made under

conditions of imperfect information, calculation down to the last decimal place is

pointless in any event.One can easilyformulate the appropriate (though not very

helpful) marginal condition for what one may call an optimallyimperfectdecision.

which requires that the marginal cost of additional information gathering or more

refined calculationbe equalto its marginal (expected)grossyield.'

* Professorat the GeorgeWashingtonUniversity,Washington.

496

ON THOUGHTLESS RATIONALITY

HAYAKAWAand VENIERIS[1977,p. 601],who otherwise depart from the

neoclass'ical paradigm, and who recognize the role of social groups in

shaping preferences and in processing information about choices, simply

assume that the resulting rules (or heuristics) are 'a useful and orderly way

of defining range of options involved in a variety of choice problems'.

The rules themselves are said to be rational because they reflect an

accumulative experience or are the beneficiaries of evolutionary developments: those who follow non-rational rules are driven out by those

who adhere to the rational ones. Hence, non-rational rules will be swept

aside by the rational ones.

The following discussion focuses on the rules of thumb (and other

devices for which the same neoclassic arguments have been advanced) to

show that (a) the empirical evidence about the rationality of these rules is

dubious, and that (b) they logically cannot serve as a basis for rational

conduct. He who lives by rules of thumb may be somewhat less or

somewhat more non-rational than those not so guided, but not very

rational by the criteria applied here and generally accepted.

Before turning to an evaluation of the thesis of rationality one step

removed, or macro-rationality,

it must be noted that this position has

been advanced for a large variety of collectively provided decision

guides. Some neoclassicists refer literally to rules of thumb, common in

the informal culture, as exemplified in such popular sayings as 'look

before you leap'. Others refer to formal rules, for example those instituted in corporate and other organization policies. Still others focus on

cognitive patterns such as heuristics or 'routines', for example the use of

abbreviations as memory aids. The same point is also applied to societal

institutions, value systems or norms of conduct ranging from those that

define one's table manners to those that guide behavior at a funeral. All

these rules 'inform' the individual how best to behave, without any

necessary calculations or forethought [MARCHand OLSEN,1984; HEINER,

1983, p. 573]. In the following discussion the term 'rules' is used to refer

to all these phenomena.

II. AN EMPIRICAL TEST: PRICE SElTING IN FIRMS

The most detailed empirical testing of the rationality of decisions by

provided rules has taken place with regard to price setting in firms. It has

497

AMITAI ETZIONI

been often observed that business executives do not set prices at the

place a simple profit maximization theory states they ought to, where

marginal costs equal marginal revenue.Instead, prices are setwhere firm

policies tell executives to set prices. But do these rules (corporate

policies), guide executives to the same maximal point?

One of the earliest and most influential studies on the use of rules is

that of HALLand HITCH[1936].They surveyed38 British firms and found

that in 30 firms the executivessaid they used full cost pricing rules. Full

cost pricing rules basically add a 'normal' or target profit margin (or, a

percent return on invested capital) to an estimate of unit costs to

establish a product's price. When the executives were asked why they

used such rules they provided three responses: (1) to deal with the

uncertainties in the estimatesof demand functions; (2)to avoid charging

too high a price (and driving away customers)or too Iowa price (in an

oligopolistic market); (3) for businessesthat sell thousands of different

items the marginal cost pricing calculations required would impose a

great burden on them.

MACHLUP[1952]takes issue with HALLand HITCH'Sconclusion, suggesting that full cost pricing leads to profit maximization. Using HALL

and HITCH'Sdata, MACHLUPargues that executives observed full cost

pricing only as long as it was consistent with profit maximization.

Further, MACHLUPnotes that looking closely at the answersthe executives provided shows that demand was in fact considered in pricing.

Firstly, some businessmen admitted that they would change price in

periods of exceptionally high or low demand. Additionally, MACHLUP

points out that the answers executivesprovided to the question of why

they used full cost pricing -fear of competitors and demand being

unresponsive to price -showed that they were taking into account

demand elasticities 'which to the economist is equivalent to marginal

revenueconsiderations' [1952,p. 71].Further, he points out that respondents were using demand signals, though the term elasticity might not

have been used. MACHLUPessentially baseshis response to HALL and

HITCHon the idea that they had expected executivesto act like economists, drawing marginal revenue and marginal cost curves and

speaking of elasticity in precise numbers. When this was not the case,

HALLand HITCHjumped to the conclusion that profit maximization was

not taking place. In effect, MACHLUPsays,the rules used proved to be

guidelines to maximization in all but the terminology used.

498

ON,THOUGHTLESS

RATIONALITY

In their influential study, CYERTand MARCH[1963] in effect supported HALL and .HITCH.They were able to predict prices at a large

departmentstore with great accuracyby discerningthree rules for

pricing in different situations: normal pricing, sales, and markdown.

While the periods in which normal prices and sales prevail take place at

regularly scheduled times, markdown is a contingency employed in the

failure or the perceived failure of these two other rules. For each

situation a common procedure is used which determines price by the

application of a predetermined, rule-based markup to a cost.

Using these rules CYERTand MARCHwere able to predict prices in a

normal pricing situation down to the penny 188 out of 197 times (a

95 percent successrate). In regard to sales pricing, 'pricing is a direct

function of either the normal price (i.e., there is a standard salesreduction in price) or the cost (i.e., there is a sales mark up rule)' [CYERTand

MARCH,1963,p.139]. They were able to predict the prices correctly down

to the penny 56 of 58 times (a 96 percent successrate).

Markdown is a situatiQn employed when feedback indicates an

unsatisfactory sales or inventory position. Even though markdown is a

contingent situation, still rules were found to govern the ways it is

treated. First, prices were not to be set below cost save as a last resort.

Second, prices were to be reduced by one third and the result carried

down to the nearest85 cents. With theserules and few others CYERTand

MARCHwere able to correctly predict prices down to a penny in 140ofl59

markdown situations (an 88 percentsuccessrate). It should be noted that

such a level of prediction is practically unknown in economics or in

other social sciences, and this study should be regarded as very compelling empirically.

It would seem that pricing policies like the aforementioned only

take into account the cost side, not studying the demand side at all. It,

hence, would seem that profit maximization is not taking place. However, NICHOLSON

[1978,p. 275]argues that despite the fact that the rules

appear to consider cost alone, demand is ultimately to be considered as

well:

'R.M. CYERTand J.G. MARCHspend considerable effort in analyzing the feedback

that the market provides for the pricing of a product. Even though prices and profit

margins may initially be set without adequate reference to demand, the reaction of the

market provides information on the true demand situation, and prices are adjusted

accordingly.'

499

AMITAIETZIONI

In short, NICHOLSONis trying to do to CYERTand MARCH what

MACHLUP did to HALL and HITCH: Use their own data to argue for the

rationality of rules. Other studies provide additional ammunition -to

both sides of the debate.

In a study that examined a group of companies over nine years,

LANZILLOTTI[1958] found that companies followed various pricing rules.

These include pricing to achieve a target return on investment; stabilization of price and mark-up margin; pricing to realize a target market

share; and pricing to prevent or meet competition. About one half of the

companies indicated that their pricing policies were based mainly upon

the objective of realizing a particular rate of return on investment in a

given year, over the long haul, or both. The question has been raised

whether a firm is maximizing profits when it sets a target rate of return

or is it setting a satisfying goal it wishes to achieve? LANZILLOTTIpoints

out that actual returns over a nine year period (1947-1955) were greater

than the target returns, at which the prices were set. He casts considerable doubt on whether the difference can be attributed to profit

maximization.

Insofar as how the profit target was set LANZILLOTTI [1958, p.931]

notes:

'The most frequently mentioned rationalizations included: (a) fair or reasonable

return, (b) the traditional industry conceptof fair return in relation to risk factors,

(c) desire to equal or better the corporation averagereturn over a recent period,

(d) what the companyfelt it could get as a long-run matter,and (e)use of a specific

profit targetas a meansof stabilizing industryprices.'

In regard to pricing for stabilization LANZILLOTTI

[1958,pp. 931-932]

develops the concept of corporate noblesseoblige which scarcely coincides with profit maximization but is more like the Marquis of Queensbury rules:

'The drive for stabilized prices by companieslike U.S. Steel,Alcoa, International

Harvester,Johns Manville, du Pontand Union Carbideinvolves both expectationof

properreward for duty done,i.e.,properprices,anda senseof noblesse

oblige.Having

earnedwhat is necessaryduring poor times to provide an adequatereturn, they will

refrain from upping the price as high asthe traffic will bearin prosperity. Likewise,in

pricing different items in the product line, there will be an effort (sustained in

individual casesby the pricing executive'sconscience)

to refrain from exploiting any

item beyond the limit setby cost-plus.'

500

ON THOUGHTLESS RATIONALITY

However, KAHN[1959]argues thatLANZILLOTTI'S

data can be used to

strong1y'supportt~e thesis that even large corporations try to maximizeprofits.

KAHN [1959, p.671] notes that the widespread use of targetpricing,

'which is really an aspect of full cost pricing, provides their [LANZILwnl, et al.]

principal evidence against profit maximization in general and the marginality description thereof in particular. This misconstruction is in confusing procedures with

"goals". Actually the target return seems above all to reflect what the executives think

the company can g~t; and as to the extent actual earnings diverge from the target it is

because the market turns out to allow more or less' [KAHN, p. 671).

In a response to KAHN's criticism LANZILLOTTI

[1959]states that the

concepts of target return and target market share seemfar more helpful

in predicting and understanding the price behavior of large corporations

than any notion of profit maximization. LANZILLOTTI

suggeststhat target

rates of return are useful quantifiable measurescorporations strive for,

while profit maximization, given its ambiguity, is likely to be an ex post

rationalization. LANZILLOTTIalso asks '... whether by stating that the

target return is really another name for profit maximization, KAHNhas

explained anything about the pricing policies of large corporations'

[LANZILLOTTI,

1959,p. 682].

KATONAconducted one of the few studies of the use of rules for

decisions involving investment rather than setting of prices. KATONA

[1975,p.323] notes that decisions on plant building and locale and

acquisition of new equipment are enduring and nonreversible. They in

general involve large sums of money; hence, one would especially

expect rational behavior in thesedecisions. 'In fact, evencasualobservation reveals numerous instances in which rules of thumb prevail and

business investment appearsto be the habitual or evenautomatic result

of certain conditions rather than the outcome of careful deliberation.'

One example is the 'follow the leader' principle: In various industries

Qnefirm is often looked upon asa leader whosedecisions are imitated by

other firms, whether or not it was justified in view of intra-industry

'differences of 'first mover' advantages. Decisions to introduce new

technology have a fadlike quality.

Without attempting to explore here further the ins and outs of these

studies, their respective merits, let alone review still others (a task

undertaken by SCHERER

[1980,pp.187-189», it is clear that the samedata

501

[II.

AMITAI ETZIONI

are interpreted by some as indicating that rules canbe used to maximize,

i.e., are fully rational, and by others to showthat rules cannot so serveand

in effect perpetuate poor practices. The obvious conclusion is that the

rules are not sufficiently specified to allow either their rational application

or -study. Luckily, we shall seeshortly, the empirical questionneed not be

answeredin order to reach a conclusion on the merit of rules.

ORGANIZATIONAL CASE STUDIES

Organizations of all kinds from armies to churches, from public schools

to prisons, promulgate large numbers of rules that direct and coordinate

the activities of their members. While these rules change over time, as

indicated by the term 'bureaucracy' often applied to organizations, their

adjustmentto changedrealities is frequently slow and far from sufficient

to ensure rational adaptation. An overview of the relevant literature

concludes: 'Rules are broadly adaptive, but there is no guarantee that

they reflect optimal, or even acceptable, solutions when new problems

arise' [STERN,1984,p.lIO]. Adaptation of rules are also reported to be

limited to the 'local' problem area and not organization-wide. And when

executivesare faced with unfamiliar, new, complex situations, they tend

to break them into components and deal with those elements that are

familiar or look familiar.

PERROW'S

[1981,p.17] study of the nuclear accident at Three Mile

Island near Harrisburg, Penn., concluded that 'it is not feasible to train,

design, or build in such a way to anticipate all eventualities in complex

systemswhere the parts are tightly coupled. They are incomprehensible

when they occur. That is why operators usually assumesomething elseis

happening, something that they understand and act accordingly'.

During the accident significant readings were not communicated to key

personnel because operators did not believe them. Thus, rules (in the

sense of 'routines')delayedproper responseto the novel situation because

people misinterpreted the situation and did not recognize it as novel.

PERROW[1981,p.25] notes: 'This is the significance of the widely

reported comment by the NRC commissioners that if only they had a

simple, understandable thing like a pipe break they would know what to

do.' Other studies show that organizational rules for collecting information tend to result in information over-load in which important items go

unnoted. It is a problem commonto mostintelligence services.This is one

502

503

ON THOUGHTLESS RATIONALITY

main reason the warning about imminent attack on Pearl Harbor was

'lost' on 'its way to Washington [WOHLSTETTER,

1962]. When new automatic gatesclosing training crossingswere introduced in Britain, a major

train disaster, known as the Hixon disaster, followed. It was established

later that slow moving vehicles could not clear the crossing ,in the

allotted 24 seconds.This fact was duly noted in a long technical manual

provided to every policy station as the new gates were introduced but

was obviously 'lost' in the avalanche of information the manual contained [TURNER,

1976; see also NEUSTADT

and FINEBERG,

1978].

NuTT [1984]studied 78 decision-making profiles of predominantly

service or voluntary organizations. He finds that managersviolate all the

rules advocated by academics for 'good' (rational) decision-making. The

managers assume away uncertainty and treat causation and desired

results as clear and specific thereby creating a false sense of security;

NUTTreports, they have a predisposition to focus their rule searchvery

narrowly as they have a 'low tolerance for ambiguity and a high need for

structure' [1984,p. 446].

CYERTand MARCH[1963,p.121]note that the searchprocessis based

initially on two simple rules, hardly rational ones: '(1) search in the

neighborhood of the problem symptom and (2) search in the neighborhood of the current alternative. These two rules reflect different dimensions of the basic causal notions that a cause will be found "near" its

effect and that a new solution will be found "near" an old one'.

An example of how such a limited search leads to a nonrational

responseis provided by HALL[1976,p. 201]in his study on the decline of

the old SaturdayEveningPost. HALLpoints out that when the managers

of the Postfaced rising production costsdue to excessiveexpansion that

resulted in depressedprofits, they responded by substantially increasing

the subscription rate. This proved to be the Posts undoing for their

readership growth leveled off and their profits were further depressedas

a significant amount of funds had to be spent on promotion merely to

hold readershipsteady.The Postthus staggeredinto the circulation wars

of the 1950sin poor financial shape and never recovered. HALLargues

,that this is a typical result of a narrow rule searchstrategy that leads one

to select an increasing of the subscription rate rather than attacking the

'underlying causalstructure of the problem (namely, the loss of control

of the annual volume and the consequentincrease in production costs)'

[HALL, 1976,p. 201].

AMITAI ETZIONI

Sometimes rules rather than change inadequately, fail to change at

all. Historically developed rules continue on long after their usefulness

is lost and when more efficient alternatives are readily available. For

example, despite the obvious fact that constant prices are the best

measureof economic activity, nominal prices are still very widely used in

financial reports, contracts and government studies [BARAN,LAKONISNK

and OFER,1980J.CYERTand MARCH[1963,p.138Jreport that frequently

the mark-ups within an industry remain the same for 40 or 50 years.

Also, rules may be rational but may be implemented incorrectly

becausetheir guidance was insufficiently specified, promulgated incorrectly, or inconsistently followed [SPROULL,

1981; BRITAN,1979J.For

example, managers often convey rules orally, and then maybe only in

response to questions, which does not ensure all will know the rules

[SPROULL,

1981,p.119J.

Finally, the study of rules as rational assumesthere are clear goals, at

least -some set goals even if somewhat unclear. However, this is often

not the case. A study of OMB under President Kennedy depicts the

difficulties the agencyhad in formulating specific budgets becausethe

President failed to set the total outlay targets [MOWERY,et al., 1980J.

Indeed, for many organizations, not just the situation is in flux but also

the goals [SILLS,1957J,rendering the use of most rules nonrational. In the

US Navy sailors were trained to step back whenevercannonswere fired

on deck long after the piece of artillery ceasedto jump back when fired.

Many of the points made in defense of the use of rules asrational, and

-the criticism -can also be made about the use of agents. For example,

neoclassicistsargue that individuals may not be able to read an insurance policy but they can pay a lawyer to read it for them and thus still

choose rationally among policies. When it is argued that people cannot

evaluate the service of agentsrationally, it is suggestedthat a 'market'

will drive out the agents that are serving the client vs. those that do not.

This would be true if the individuals could evaluate the advice and if

there was a competitive market among agents. Often, neither is true.

Told, for example, that life insurance X is better than Y, how manytimes

do people die and come back to evaluate their death benefits? The same

holds for many other such products from insurance for catastrophic

illness or nursing homesto legal advice in the caseof a divorce. A study

of patients' evaluation of their physician shows (a) they are unable to

evaluate them rationally and (b) are selecting them on the basis of

504

ON THOUGHTLESS RATIONALITY

irrelevant cues (such as the opulence of their reception rooms). The best

predictor of the agent to sell one insurance is not hi~ or her competitivenessbut how much the agentis able to evoke a senseof affability in the

client [CHESTNUT,

1977]. To further discuss the pros and cons of the

rationality of the use of agents, and the parallelism and divergences inthe

rules sub-theory and the agents sub-theory, will cause a major

digressionand hence is avoided. Agents are mentioned only to add themto

a socio-economic researchagendacharted here but not implemented.

IV. RULES CANNOT BE USED RATIONALLY

The empirical evaluation of the use of rules seemsinconclusive. Despite

severalsizable studies, conducted over decades,it is not possible to draw

a firm conclusion whether or not rules enable their followers to act

rationally, because, it seemsthe theory is insufficiently specified. As a

result, the same evidence is interpreted by some as supporting, and by

others as negating, the same hypothesis. While several case studies

provide considerable plausibility to the thesis that the application of

rules often leads to non-rational behavior, such studies, by their very

nature of being 'cases',are not fully compelling, especiallyto those who

are used to quantitative data. There is, though, a way to resolvethe issue

because one can show that rules in many situations cannot provide

rational guides. It is a matter of sheerlogic, not of empirical evidence.

The discussionturns next to provide severalreasonsin support of the

position that the use of rules is a priori non-rational in many circumstances.

1. Rules are typically advanced in isolation from one another rather

than part of an overarching system. As a result they tend to ignore the

fact that an efficient response to most challenges in the real, complex

world require taking into account multiple considerations.

At the same time, there is no reason to deny that in some instances

some simple rules prove very useful, at least until their use becomes

widely known. The IRS is using numerous guidance rules, collated into

ClassificationHandbook IRM 41(12)0.For example, the IRS pays special

attention to children claimed as exemptions by separated parents

because they are often claimed by both while only by one is proper.

Hence, while one may expect, becauseof the a priori reasonsprovided

505

AMITAI ETZIONI

above, that rule guided behavior will often be quite non-rational; this

generalization cannot be applied to every instance. As to the question,

under what condkions the application of rules is relatively more

rational. This seemsto be a matter about which relatively little is known.

2. When individuals are provided with more than one rule, those

rules often conflict with one another. For example, investors are told to

'buy low and sell high' (an ambigous rule by itself, becauseno definition

of either 'high' or 'low' is included and hencethe rule invites investors to

project their feelings on the situation). Sometimes'high' or 'low' refers to

pricelearnings (PIE) ratios. However, what is a high ratio is not agreed

and people are advised to invest in stocks of 'high-growth' corporations

despite the fact that their PIE ratios are often infinite because they

initially show no profit at all. Investors are also advised 'notto fight thetape'

and to 'let their profits run but cut their lossesshort'. These rules

suggestthat if prices of stock move up, investors ought to expect them to

move still higher, while if the prices fall- and hence are relatively lowinvestors ought to bailout. These rules are incompatible with one

another.

3. Rules are typically formulated as if they were universal truths,

applying to all circumstances, to all times, and to all people. Three

examplesillustrate the fallacy of universality: Rule number 810from the

only book exclusively dedicated to 'rules of thumb' [PARKER,

1983]reads:

'Don't pay more than twice your average annual income for a house.' It

neglects to mention if gross or net income is at issue and the effects of

one's tax status. For example, given current tax laws it makes much more

sensefor a person with a high income but few other deductions to violatethe

rule than one with lower income or many deductions. Also, different

tax laws apply to those who are 55 years or older than to younger persons

-for instance, the one-time exclusion on capital gain from the sale of

one's house.

Rule number 96 warns those who launch a political campaign that

'a certain percentage of voters will be for or against you based purely onparty.affiliation

Only a small percentageof voters are truly independent

and will consider you without bias'. First, like the buy-low, sell-high rule,this

one contains vague terms such as 'certain percentages' and 'truly'.

To the extent that its meaning is that political affiliation is much more

important than the person, it holds much less now than, say, twenty

years ago.

506

ON. THOUGHTLESS RATIONALITY

When the value of the dollar on foreign exchangesdropped 20 percent early in 1985 many economists feared that this would exacerbate

inflation in the United Statesbecausea 10percent drop was expected to

add 1.5 percent to 2 percent to inflation. But JAMESE. ANNABLE,chief

domestic economist at the First National Bank of Chicago, stated that

this will not be the casebecause'rules of thumb that applied in the 1970s

don't apply in the 1980s'[New York Times,March 31, 1983].He did not

elaborate if the rules must be adapted every decade, or more often or

how one tells before the fact if they still apply.

Ample examples of the application of rules out of context is found in

the frequent use of neoclassical economics in policy making. Much of

neoclassical economics is formulated on the assumption that it takes

place in a fully competitive market. However, suchmarkets are often not

available, not evenapproximated. Yet rules formulated for full competition are applied, often without even an attempt at adaptation, to the

fundamentally different situation or context.

4. When rules conflict people will follow the rule that coincides

with their subjective estimates and own values. For instance, a less risk

averse person may follow rule number 102: 'Don't enter a poker game

unless you have forty times the betting limit in your pocket'. The more

risk averse may pick rule number 103: 'Don't enter a poker game unless

you have sixty times the betting limit in your pocket' [PARKER,1983,

p.17].

Another pair of conflicting rules is discussed by KINDLEBERGER

[1985,p.l] in his essay on the social responsibility of corporations. He

writes: 'The least of the issue is the clash between"When in Rome, do as

the Romans do", and "To thine own self be true"'. Many a corporation

chooses between those not according to some cost benefit study but in

line with its established culture.

5. Another way to see that rules that culture offers are not rational is

to see that they are often not sufficiently specific to provide guidance.

Barron's publishes a weekly polling the 'sentiments' of traders in Treasury bonds and bills, expressed in percentage 'bullish'. But it always

adds the note that 'high readings usually are signs of market tops, low

ones, market bottoms'. Neither high nor low (or used) are defined.

Hence, in effect, the weekly table provides a typical two-faced, highly if

not completely, ambiguous rule. Ifbonds go up, the poll is 'validated'; if

not -the note is. Together they provide at best a very vague guidance.

507

V.

AMITAI ETZIONI

,

'No price is too low for a bear or too high for a bull' notes Barron's

[11-10-86,p.16]. Many rules are such.

Editing and writing are taught by rules but those who have taken such

a course can attest to how bewildering such rules often are. NORMAN

MAILERregularly violates most rules taught in courses on the writing of

proper English but is considered a very crafty author (reference is to

style, not content). KENNER[1985,p.I] writes: 'The plain style has been

hard to talk about, except in circles.. .' SWIFT,KENNER

reports, refers to it

as 'proper words in proper places' but KENNERpoints out that SWIFT

does not explain 'how to find the proper words or to identify the proper

places to put them into' [KENNER,

1985,p.I].

6. Psychologistshave shown that people often evaluate the validity

of messagesusing rules such as 'length implies strength', 'consensus

implies correctness', 'expert's statements can be trusted' [CHAIKEN

and

STANGOR,

1987].The knowledge that people are vulnerable in this way is

used to fashion persuasiveadvertising. For example,actors who impersonate doctors are used to 'recommend' over the counter drugs to buyers

who hardly need them. That is, rules people follow in their decisionmaking are used to deflect them from rational decision-making rather

than to help.

EXPERIENCEAND EVOLUTION

People are said to drop non-rational rules and retain rational ones as

their personal or collective (shared) and accumulative experience

teaches them which rules work. Actually the users of rules cannot judge

or evaluate them any better than the options they faced to begin with and

which led them to use rules, for basically the same reasons they cannot

make a rational decision to begin with. (WINTER [1975Jmade the same

point about information costs.) The fact that heuristics are systematically biased and hence constitute a poor guide to decision-making is well

established. Evidence in support of non-learning is seen in that people

keep making the same numerous systematic mistakes in evaluating

probabilities using the same biased heuristic. Over the course of a

lifetime their experience does not suffice to teach them to modify the

rules [TVESKYand KAHNEMAN,1974,p.1130J. In effect SKINNERprovides a

rather compelling model for how rules may be reinforced even when

they are quite incompatible with the evidence.

508

O~ THOUGHTLESS

RATIONALITY

Too much information to process, limited intellectual capabilities,

and values and em,otionsall curb the individual's ability to assessrules as

it limits their ability to evaluate options. It might be said that there are

many fewer rules than options and hence they are easier to 'process'.

However, the evaluation 'of most rules is much more difficult than that of

most options. Compare, for example, the dilemma of a chessplayer who

must decide how to proceed in a particular game and situation vs.

judging the rule, say, that one ought to develop one's forces (how long?)

before one attacks. Compare an executive who must determine at what

level to set the price of a specific product in a specific market, vs. to

determine which pricing policy is the most effective. We saw already the

difficulties professional economists have in coping with the latter question after many years of study and arguments.

Collectively provided rules by society, carried in the culture, are said

to be rational. As TODA[1980]puts it, much learning takes place on the

'species' level rather than that of the individual. One reasongiven is that

individuals -who are rational- created theserules. 'Norms and Institutions were presumably created by men... ...and there is no a priori

reasonto suppose these men were any the less rational when they were

constructing institutions than they were in their daily lives' [HEATH,1976,

p. 63]. For the viewpoint presented here, the samestatementis to be read

in the opposite way the author intended: Peopleare sub-rational in their

daily life; there is no a-priori reasonto believe the rules they promulgate

will be rational. As CROSS

[1983,p.17] writes: 'It is one thing to observe

that choice making in practice seems to be governed by simple and

inexpensive decision rules; it is quite another to show how those rules

that are in use have come to be selected in preference to aU of the other

simple rules that could have come to be used instead.' Also, however

rules are originally made, as we have seen, they tend to ossify and lag

behind changes in the environment.

Rules that organizations promulgate have been studied above. But

organizations (and institutions) themselvesare viewed as a mechanism

that limits the need to choose by providing a rational context for

'decisions. Traditionally, organizations, especially firms, have been

viewed by sociologists as social units that evolve in part in ways the

participants are unaware of or do not desire. Originally, an organization

mayhave been selectively designed rationally as an efficient means to

implement its particular goal or set of goals. But, organizational studies

509

510

AMITAI ETZIONI

show, as rules get entrenched and vested interests in them evolve, poiitics

grows, informal cultures arise, and the organization ceases to be an

efficient tool, if it ever was.

Evidence cited above seems to amply support this view. However, in

recent years, neoclassicists have formulated a 'new economics of organizations' drawing on a COASE[1937] article and WILLIAMSON'S[1975, 1985]

work. Accordingly, firms arise when it is efficient for them to arise; when

organizing production through the price mechanism (or market)

becomes too costly. Most of the writing along these lines is highly

deductive, ('Firms must have arisen, because.. .'). Empirical evidence is

very scant.

Some neoclassicists have extended the view of rules as efficient

guides from organizations to whole polities and even societies, and to

the march of history. NORTH[1981]for example argues that states are akin

to firms in a market: They seek to maximize revenue growth subject. to

various constraints (for example, technical knowledge). The rise and fall

of states is next studied in terms of changes in constraints. For example,

states will increase taxes up to the point the costs of the transaction

involved become too high or citizens' allegiance too low. And, states

develop various mechanisms (for example, tax farming) that reflects

efficient adaptation to the constraints they face. (For further discussion

and critical review of this approach, see MARCH and OLSEN[1984] and

DOUGLASand WILDAVSKY[1982].)

Finally, it has been argued that rules are rational due to evolutionary

selection. For example, HEINER [1983, p.586] writes: '... evolutionary

processes have long been interpreted as one of the key mechanisms

tending to produce optimizing behavior, or conversely, optimizing

behavior will predict the behavior patterns (or rules, AE) that will

survive in an evolutionary process... [HEINER, 1983, p.560]. And

'appropriately structured behavioral rules... will evolve to the extent

that selection processes quickly eliminate

poorly administered

behavior'. FIELD [1984] argues that there is a limited universe of possible

norms (or rules). Members of social groups, organizations, or polities

work out together -using game theory strategies -which rule to share

and which are the most efficient ones. See also ULLMANN-MARGALIT

[1977].

For the viewpoint advanced here, the notion of a state of nature, in

which there are individuals -fully formed and able to render decisions -

511

ON THOUGHTLESS RATIONALITY

before norms existed, is rather flawed, not only historically, but also as a

heuristic~.Individuals are not well formed unless they are members of

collectivities, which in turn contain nom1s. While there is little to be

gained by pursuing the question who was first at the creation of the

human realm, an I or a We, if the question must be broached, the

anthropological literature leaves little doubt that collectivities, within

which there was little or no individual identity awarenessand autonomous action, preceded the I's. Collectivities can hardly be the product of

rational individuals who preceded them.

Moreover, the conditions for evolutionary selections of rules often do

not exist. Among most organizations there often is no competitive

market; good schools do not shove poor schools out of business; poorly

run nursing homes are found next to well run ones and so on. Even the

existence of such competition among firms is historically rare and its

scope even in the West is much more limited than it is often acclaimed.

And, the environment to which firms and other organizations must

adapt, is largely composed of other firms like themselves, not a set

nature. We thus seefollowers of 'good' and 'bad' rules functioning right

next to one another in the same environment and reliance on rules is

hence no assurance that the rules are rational. Also, as SIMONargued,

evolution leads to local or sub-optimal selection; there is no reason to

suppose evolution leads to optimal rules [SIMON,1982,p. 53ft].

What holds for organizations, holds even more true for societies.

There obviously is no market for societies in which the efficient ones

drive out the others. Societies with extremely inefficient institutions or

regimes,such asthe Soviet mega-bureaucracy,survive for decades.Very

few societies evercollapse; instead, they change -not necessarilyfor thebetter!

-very gradually and slowly, and continue to be quite inefficient

even if they give up some of their most inefficient features, without

acquiring worse ones. Clearly evolution is not working on this level

either.

In short, the argument in favor of automatic or systemicallyprovided

rationality, one in which individuals may not think or deliberate yet act

rationally, is poorly supported by facts and is logically untenable. The

fact that it is continuously to be advanced is itself an indicatiqn that

rules, at least in the form of theorems, survive for other reasonsthan that

they are logical or empirically supported.

AMITAI ETZIONI

REFERENCES

BARAN,ARIE; LAKONISHOK,

JOSEF

and OFER,MARON R.: 'The Informational Content

of General Price Level Adjusted Earnings: Some Empirical Evidence', The

Accounting Review,Vol. 55 (1980),pp. 22-35.

Ba"on's, Nov. 10, 1986,p.16.

BAUMOL,WILLIAM J. and QUANDT, RICHARDE.: 'Rules of Thumb and Optimally

Imperfect Decisions', American Economic Review,Vol. 54 (1964),pp.23-46.

BRITAN, GERALDM.: 'Evaluating a Federal Experiment in Bureaucratic Reform',

Human Organinizations, Vol. 38 (1979),pp. 319-324.

CHAIKEN,SHELLYand STANGOR,

CHARLES:'Attitudes and Attitudinal Change', To

appear in the Annual Review of Psychology,Vol. 38 (1987).

CHESTNUT,

R. W.: Information Acquisition in Life Insurance PolicySelection: Monitoring

the Impact of Product Beliefs, Affect Toward Agent, and External Memory, Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Psychology Department, Purdue University, 1977.

COASE,RONALD:'The Nature of the Firm', Economica,Vol. N.S. 4(1937), pp. 386-405.

CROSS,JOHNG.: A Theory of Adaptive Economic Behavior, Cambridge: Cambridge

Cambridge Univ. Press,1983.

CYERT,RICHARDM. and MARCH,JAMESG.: Behavioral Theory ofthe Firm, Englewood

Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1963.

DouGLAs, MARYand WILDARSKY,

AARON:Risk and Culture: An Essayon the Selection

of TechnologicalEnvironmental Dangers,Berkeley: Univ. of California Press,1982.

FIELD, ALEXANDERJAMES: 'Microeconomics, Norms and Rationality', Economic

Development and Cultural Change,Vol. 32 (1984),pp.683-711.

FRANK,ROBERTH.: 'Shrewdly Irrational', To be published in Sociology Forum, 1987.

HALL, ROGERI.: 'A System Pathology of an Organization: The Rise and Fall of the Old

Saturday Evening Post', Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol.21 (1976), pp.

185-211.

HALL, R.L. and HITCH,C.J.: 'Price Theory and Business Behavior', Oxford Economic

Papers,Vol. 2 (1939),pp.12-45.

HAYAKAWA,HIROAKIand VENIERIS,

YIANNIS: 'Consumer Interdependence via Reference Groups', Journal ofPolitical Economy,Vol. 85 (1977),pp. 599--615.

JIEATH,ANTHONY: Rational Choice and Social Exchange: A Critique of Exchange

Theory, Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press,1976.

HEINER,RONALDA.: 'The Origin of Predictable Behavior', American Economic Review,

Vol. 73 (1983),pp. 560-595.

KAHN, ALFRED:'Pricing Objectives in Large Companies: Comment', American Economic Review,Vol. 49 (1959),pp. 670--678.

KATONA,GEORGE:Psychological Economics. New York: Elsevier, 1975.

KENNER,HUGH: 'The Politics of Plain Style', New York Times Book Review, Sept 13,

1985,pp.I, 39.

KINDLEBERGER,

CHARLES

P.: Social Responsibility of the Multinational Corporation,

Remarks for a Panel at the Bentley College Conference in Business Ethics, Oct. II,

1985.

512

ON THOUGHTLESS RATIONALITY

LANZILLOTTI,ROBERT

F.: 'Pricing Objectives in Large Companies', American Economic

Review,Vol. 48 (1958),pp.921-940.

LANZILLOTTl,ROBERT-F.:'Pricing Objectives in Large Companies: Reply', American

Economic Review,Vol. 49 (1959),pp. 679-686.

MACHLUP,FRITZ: The Economics ofSellers' Competition, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press,1952.

MARCH,JAMES

G. and OLSEN,JOHANP.: 'What Administrative Reorganization Tells Us

About Governing', American Political ScienceReview,Vol. 77 (1984),pp. 281-296.

MOWERY,DAVID C.; KAMLET,MARK S. and CRECINE,JOHNP.: 'Presidential Management of Budgetary and Fiscal Policymaking, Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 95

(1980), pp- 395-425.

NEUSTADT,R.E. and FINEBERG,

H.V.: 'The Swine Flu Affair: Decision Making on a

Slippery Disease', Washington, D.C.: US Dept. of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1978.

New York Times,March 31,1983.

NICHOLSON,WALTER: Microeconomic Theory, 2nd ed., Hinsdale, Illinois: Dryden

Press,1978.

NORTH, DoUGLASC.: Structure and Change in Economic History, New York: W.W.

Norton & Co., 1981.

NuTT, PAULC.: 'Types of Organizational Decision Processes',Administrative Science

Quarterly, Vol. 29 (1984),pp. 414-450.

PARKER,TOM:Rules of Thumb, Boston: Houghton/Mifflin,

1983.

PERRow,CHARLES:'Normal Accident at Three Mile Island', Society, Vol. 18 (1981),

pp.17-26.

SCHERER,

F. M.: Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance, 2nd ed.,

Boston: Houghton/Mifflin,

1980.

SILLS,DAVID L.: The Volunteers: Means and Ends in a National Organization, G1encoe,

IL: The Free Press,1957.

SIMON,HERBERT:The Sciences of the Artificial, 2nd ed., Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press,

1982.

SPROULL,LEE S.: 'Managing Education Programs: A Microbehavioral Analysis',

Human Organization, Vol. 40 (1981),pp.113-122.

STERN,PAULC. and ARONSON,ELLIOT(eds.): Energy Use: The Human Dimension, New

York: W.H. Freeman and Co., 1984.

TODA,MASANAO:'Emotion in Decision-Making', Acta Psychologica, Vol.45 (1980),

pp.133-155.

ThRNER,BARRYA.: 'The Organizational and Interorganizational Development of

Disasters', Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 21 (1976),pp. 378-397.

'J\IERSKY,

AMos and KAHNEMAN,DANIEL: 'Judgement Under Uncertainty: Heuristics

and Biases', Science,Vol. 184 (1974),pp.1124-1131.

UL~MAN-MARGALIT,

EDNA: The Emergence of Norms, Oxford: The Clarendon Press/

Oxford Univ. Press, 1977.

WILLIAMSON,OLIVERE.: Economic Institutions of Capitalism, New York: Free Press,

1985.

513

AMITAI ETZIONI

WILLIAMSON,OLIVERE.: Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications,

New York: The Free Press,1975.

WINTER,SIDNEYG.: 'Optimization and Evolution in the Theory of the Firm', in: DAY,

RICHARDH. and GROVES,

ThEODORE

(eds.), Adaptive Economic Models, New York:

Academic Press, 1975,pp. 73-118.

WOHLSTE1TER,

ROBERTA:Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision, Stanford, CA: Stanford

Univ. Press, 1962.

SUMMARY

The recognition of the existenceof imperfectinformation in decision-makingand the

cognitive limitations of the humanmind put various assumptionsof the neoclassical

economic paradigm in doubt. Neoclassicaleconomistsresponded by arguing that

decision rules, or rules of thumb, canbe usedto render decisionwithout processing

information. Further, neoclassicistshave suggestedthat rational rules compete

againstand drive out irrational ones.This paperfocuseson the use of rules of thumb

and posits that the empirical evidenceaboutthe rationality of theserules is dubious

and that they logically cannotserveas a basis for rational conduct.

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG

Die Erkenntnis,dassbei Entscheidennicht vollstandige Infonnation vorhandenist,

sowie das Wissenum die kognitiven Beschrankungen

des menschlichenVerstandes

lassenan verschiedenenVoraussetzungen

des neoklassischenParadigmaszweifeln.

Neoklassische6konomen entgegnen,

dasssichEntscheidungsund Faustregelnauch

ohne vollstandige Infonnation anwendenlassen.Weiter gehensie davon aus,dass

rationale Regeln mit irrationalen Regelnkonkurrierenund letztere verdrangen.1m

Artikel geht es um das Anwendenyon Faustregeln.Es wird gezeigt,dassdie empirischeEvidenzfur die Rationalitatder Faustregelnzweifelhaftist und dassdieseRegeln

nicht als Grundlage fur rationalesBenehmendienenkonnen.

RESUME

La reconnaissancequ'il existedansIeprocessusde prendreune decisiondesinfonnations imparfaites et deslimites de l'esprit humain,a mis en doute plusieurs suppositions du schemaeconomiqueneo-classique.Les economistesneo-classiquesont

repondu en soutenantque par regle$de decision, ou procedesmecaniques,il est

possible,memesansopererl'infonnation, d'arriver a une decision. En outre,ils ont

suggereque les reglesrationnelles sont en competitionayec et repoussentles regles

irrationnelles. Cetteetudeseporte sur l'emploi desprocedesmecaniques,etconstate

quel'evidenceempiriquedelarationalitedecesreglesestdouteuseetqu'ils nepeuvent

logiquementpas servircommebasede conduite rationnelle.

514