trafficking in human beings in conflict and post

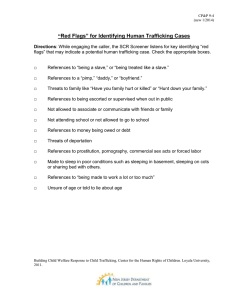

advertisement