Echocardiography in the ICU: time for widespread use!

Intensive Care Med (2005) 32:9–10

DOI 10.1007/s00134-005-2833-8

E D I T O R I A L

Bernard P. Cholley

Antoine Vieillard-Baron

Alexandre Mebazaa

Echocardiography in the ICU: time for widespread use!

Received: 24 October 2005

Accepted: 24 October 2005

Published online: 16 November 2005

Springer-Verlag 2005

This editorial refers to the article http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00134-

005-2834-7

B. P. Cholley ( ) ) · A. Mebazaa

Departement d’Anesthsie-Ranimation,

Hpital Lariboisire, Assistance Publique-Hpitaux de Paris,

2 rue Ambroise Par, 75475 Paris cedex 10, France e-mail: bernard.cholley@lrb.aphp.fr

Tel.: +33-1-49958085

Fax: +33-1-49958073

A. Vieillard-Baron

Service de Ranimation Mdicale,

Hpital Ambroise Par, Assistance Publique-Hpitaux de Paris,

9 avenue Charles de Gaulle, 92104 Boulogne, France

As emphasised by Price et al. in their review published in this issue of Intensive Care Medicine [1], a large number of cardiac conditions can be diagnosed and analysed by echocardiography in critically ill patients. Over the past

15 years, many intensivists, aware that echocardiography was a powerful diagnostic tool, attended cardiac ultrasound courses and training. In parallel, a number of intensive care units (ICUs) have adopted echocardiography as part of their armamentarium for cardiovascular evaluation.

However, echocardiography in the ICU is not only useful for analysing cardiac anatomy and function in critically ill patients, but it can also be a life-saving tool.

When a physician is confronted with a patient in shock, no other technique can provide clues to the underlying problem there at the bedside, within a few minutes, noninvasively, and with better reliability. Which parameter will tell for sure how to choose between fluids or diuretics, vasodilators or inotropes? Clinical features alone are sometimes not enough, even in the most experienced hands, to provide a good understanding of the patient’s circulatory status [2]. It has already been shown in cardiac failure patients that echocardiography is by far easier and faster than pulmonary artery catheterisation for providing key haemodynamic information that will help the physician select the appropriate therapeutic strategy

[3]. Although only a limited number of studies have compared echocardiography and pulmonary artery catheterisation in a randomised manner, nobody challenges the obvious usefulness of echocardiography, especially in haemodynamically compromised patients [4].

In contrast to the sophistication and refinement of a complete cardiac examination, echocardiography in a patient with shock of unknown origin is aimed only at providing rough, but crucial, information to decide on treatment: Is the left ventricle severely hypokinetic, as in cardiogenic shock? Is the right ventricle outrageously dilated and hypokinetic with a rightward shift of the interventricular septum, as acute cor pulmonale? Is there a massive valvular regurgitation that was not present before? Is there a large pericardial effusion that can be linked to a clinically suspected tamponade?

Of course, in some cases intricate conditions can be confounding. For instance, hypovolaemia may be difficult to recognise in a patient with dilated cardiomyopathy, and a dilated right ventricle in a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease does not mean he has pulmonary embolism. However, there is no doubt that in a large number of patients with life-threatening shock, visualisation of obvious abnormalities on echocardiography will lead to a quicker and more appropriate therapeutic choice compared with the same situation without echo.

Both reduction in the delay to treatment and avoidance of undue therapies can have beneficial effects on patient outcome, representing the main reason to have a dedicated ultrasound machine in every ICU.

Patients in shock are admitted at any time, sometimes at night when only one physician is in charge of the entire

ICU. It is our opinion that echocardiography should be available 24 h a day in every ICU. Ideally, physicians

10

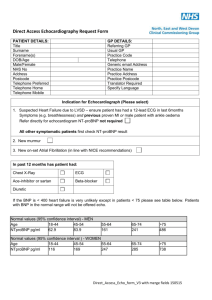

Fig. 1 The “pyramid” of echocardiography skills in the intensive care unit (ICU). At the top are trained operators who have gone through formal training and board certification. They are in charge of teaching all other ICU physicians, especially those who are minimally trained to obtain “vital” information ( base of the pyramid ). In the middle are the physicians who are in the process of preparing their echocardiography certification and who are usually able to acquire additional relevant information using echocardiography. ( CO cardiac output, PAP systolic pulmonary artery pressure,

ACP acute cor pulmonale, LV left ventricle, EF ejection fraction) should be able to use it to optimise their diagnostic accuracy and speed initiation of appropriate treatment.

Unfortunately, not all intensivists are trained echocardiography operators yet. However, it seems reasonable to suggest that every critical care physician should at least be able to perform a basic ultrasound examination of the heart when the aetiology of shock is not 100% clear.

Fortunately, the most severe shocks are usually associated with caricatural images that are easy to interpret. Conversely, when echocardiographic abnormalities are more subtle, the situation is probably less severe, and a delay in therapeutic initiation is less likely to be deleterious; in such cases it is acceptable to wait for a trained operator to try to obtain a more thorough analysis of the situation.

Each critical care team could be organized in a pyramidal manner with respect to echocardiography skills

(Fig. 1). At the top of the pyramid, each unit should have one or more fully trained operators to whom any questions regarding echocardiography interpretation can be referred. These operators should be able to accomplish all the tasks described in the review [1], but they are not supposed to substitute for the cardiologist; critical care practice does not provide expertise with specific cardiologic issues such as detailed valvular analysis, stress echocardiography, and so on. On the other hand, haemodynamic assessment and description of ventricular function are part of routine examinations in the ICU.

These trained operators can also control and validate echo studies performed by less experienced colleagues.

At the base of the pyramid are the physicians who have followed no specific formal echocardiography training outside of their unit. They should all be able to operate the ultrasound system’s basic functions (bidimensional transthoracic echocardiographic and video recording), and they should be trained to recognise severely hypokinetic left ventricle, right ventricular dilatation, collapsed or dilated inferior vena cava, and pericardial effusion. This can be achieved by showing them a selection of typical recordings [5].

Between the base and the top of the pyramid are the physicians who are currently following formal echocardiography training but have not yet obtained their certification.

In France, a specific echocardiography course for intensivists and anaesthesiologists has recently been added to the classic cardiologic echocardiography training, focusing on issues related to haemodynamic assessment in critically ill patients under mechanical ventilation. This adaptation to the practice of echo in the critical care environment should help create a “critical mass” of trained operators to disseminate the use of echocardiography in every ICU in the near future.

References

1. Price S, Nicol E, Gibson DG, Evans T

(2005) Echocardiography in the critically ill: current and potential roles.

Intensive Care Med. DOI: 10.1007/ s00134-005-2834-7

2. Eisenberg PR, Jaffe AS, Schuster DP

(1984) Clinical evaluation compared to pulmonary artery catheterization in the hemodynamic assessment of critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 12:549–553

3. Kaul S, Stratienko AA, Pollock SG,

Marieb MA, Keller MW, Sabia PJ

(1994) Value of two-dimensional echocardiography for determining the basis of hemodynamic compromise in critically ill patients: a prospective study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 7:598–

606

4. Joseph MX, Disney PJ, Da Costa R,

Hutchison (2004) Transthoracic echocardiography to identify or exclude cardiac cause of shock. Chest

126:1592–1597

5. Jardin F, Vieillard-Baron A, Beauchet

A: http://www.pifo.uvsq.fr/hebergement/webrea