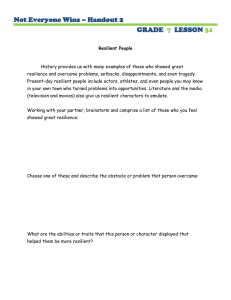

RIRO Resiliency Guidebook - Reaching IN...Reaching OUT

advertisement