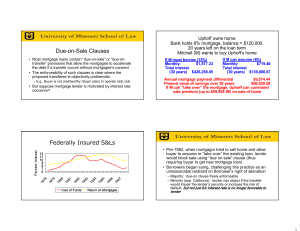

Enforceability of Mortgage Due-On-Sale Clauses

advertisement