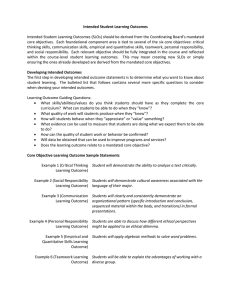

Evaluating Student Learning

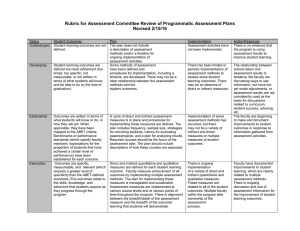

advertisement