Patel (Respondent) v Mirza (Appellant)

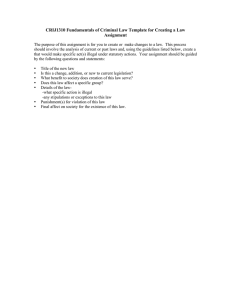

advertisement