technology-enhanced learning

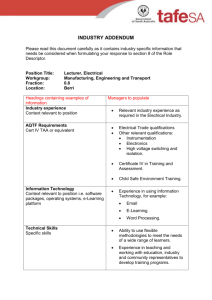

advertisement