2015 faculty task force on the undergraduate academic experience

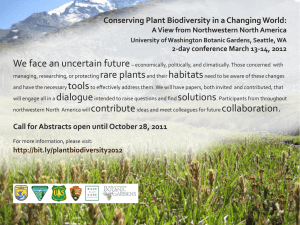

advertisement