A Sectoral Approach to News Shocks

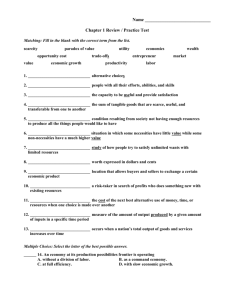

advertisement