How batteries discharge: A simple model

advertisement

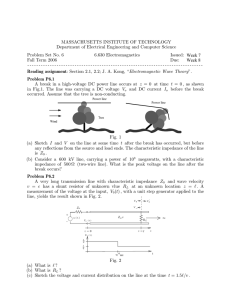

How batteries discharge: A simple model W. M. Saslowa兲 Department of Physics, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas 77843-4242 共Received 7 June 2007; accepted 22 November 2007兲 A typical battery is a set of nominally identical voltaic cells in series and/or parallel. We consider the discharge of a single voltaic cell. As the cell discharges due to current-carrying chemical reactions, the densities of the chemical components decrease, which leads to an increase in the internal resistance of the voltaic cell and, upon discharge, a decrease in its terminal voltage and current. A simple model yields behavior similar to what is observed, although accurate battery models are more complex. © 2008 American Association of Physics Teachers. 关DOI: 10.1119/1.2826658兴 I. INTRODUCTION Most introductory physics textbooks give an oversimplified, black-box discussion of voltaic cells, with the internal electrical resistance r placed outside of the cell, and the electromotive force 共emf兲 E treated artificially as a volume pump within the cell’s electrolyte, bounded by the two electrodes.1–3 On going around a discharging circuit the voltage profile in this model has an unphysical linear rise across the volume of the cell and an unphysically-located linear fall in voltage across the externally placed “internal” resistance. The unnatural spatial separation of the voltages associated with this incorrect model of the emf and the internal resistance is necessary in order to distinguish these voltages, because in one dimension they both vary linearly with the spatial coordinate. A reasonably correct treatment of a discharging cell has a linear decrease in voltage within the electrolyte and two voltage jumps at the electrode-electrolyte interfaces. Hence we do not need to separate the emf of the voltaic cell from its internal resistance; they have intrinsically different spatial dependences. One of the major defects of the black-box model is its inability to explain why a AAA cell and a D cell have the same emf. In particular, the volume pump model suggests that the D cell emf should vastly exceed the AAA cell emf, in contradiction to common experience. Although the physics of voltaic cells seems to have become lost to the physics community, voltaic cells were treated correctly in physics texts as late as the 1940’s.4,5 As has been discussed,6 a realistic model of a voltaic cell must incorporate the fact that 共to use an archaism兲 the “seat of emf” of a voltaic cell, which leads to voltage jumps at the two electrode-electrolyte interfaces, is due to chargetransferring chemical reactions at the two electrodeelectrolyte interfaces.7–9 The phrase “two surface pumps and an internal resistance” conveniently and reasonably accurately describes a voltaic cell.6 Previous work accounted for surface resistances at the electrode-electrolyte interfaces, where the electric currentproducing chemical reactions occur. These additional resistances lead to three sources of internal resistance associated with the voltaic cell: the electrolyte and the electrodeelectrolyte interfaces.6 For a lead-acid cell, the effect of the electrode-electrolyte interfaces is negligible; a typical leadacid cell is effectively discharged when the sulfuric acid has become depleted to the point where the terminal voltage of the cell falls to ⬇1.7 V, below which the devices that it drives normally will not operate.10 218 Am. J. Phys. 76 共3兲, March 2008 http://aapt.org/ajp The present work shows how the increase in internal resistance due to discharge leads to a qualitative and semiquantitative explanation of how a battery 共properly, a single voltaic cell within the battery兲 becomes ineffective. For the lead-acid cell the internal resistance r is taken to have a fixed part rs from the electrode-electrolyte interfaces and a part re from the electrolyte, which is inversely proportional to the amount 共“charge” Q兲 of sulfuric acid in the cell. This mass decrease in proportion to the amount of electrical discharge is a version of Faraday’s law of electrolysis. The cell emf E is taken to be fixed, although by Nernst’s equation it is somewhat affected by the state of the electrolyte.11 This model has the property that when the external load resistor RL dominates the internal resistance r, the current is nearly constant and causes a nearly uniform 共in time兲 increase in the internal resistance, which causes the current to have a slow linear decrease with time. On the other hand, when r dominates 共for example, because the sulfuric acid has become nearly depleted兲, the current I decreases exponentially with time. There is an intermediate regime where the battery discharges rapidly; the crossover is characterized by a change in the sign of the curvature of the terminal voltage ⌬VT versus time, at which time the battery is effectively useless. All this behavior is in qualitative agreement with experiment. II. INTERNAL RESISTANCE To provide a self-contained discussion we present in more detail than in Ref. 6 a derivation of the net internal resistance of a voltaic cell in terms of the electrolyte resistance and the two electrode-electrolyte-interface resistances. We neglect nonfaradaic 共or noncharge-transferring—e.g., ordinary兲 chemical reactions at the electrode-electrolyte interfaces, which are responsible for the slow discharge of voltaic cells that are on an open circuit.12 We will assume that the discharge is slow, corresponding to the use of the headlights of a car. We will also neglect the rearrangement of ions that can occur within a voltaic cell.13 If such rearrangement occurs, both the electric field and diffusion contribute to the motion of ions within the cell, and the problem becomes considerably more complex and unsuitable for discussion at the introductory level. We treat the two electrode-electrolyte interfaces as supporting chemical reactions that provide emfs E1 ⬍ E2, which tend to drive current out of the cell, so that for the cell of Fig. 1 the net rightward emf E is, by Volta’s law for electrodes, © 2008 American Association of Physics Teachers 218 Fig. 1. Model of a voltaic cell. The asymmetry indicates that the electrodes are distinct, with the larger electrode having the larger emf. ⌬V2 = V2T − V2e, ⌬V1 = V1T − V1e, ⌬Ve = V2e − V1e. E = E2 − E1 . 共1兲 When the cell discharges, positive current I will leave the cell by electrode 2 and enter the cell by electrode 1. The values of E1, E2, and thus E1 are determined by the cell’s chemistry. Let the electrodes be characterized by surface resistances r1 and r2 and the electrolyte by the resistance re. The voltages of the terminals are V2T and V1T, and the electrolyte voltages adjacent to the respective terminals are V2e and V1e. We define ⌬V2 = V2T − V2e, ⌬V1 = V1T − V1e, ⌬Ve = V2e − V1e . 共2兲 We use these definitions of the voltage differences and the convention that positive current is to the right and apply Ohm’s law to each electrode and to the electrolyte. The result is I= E2 − ⌬V2 r2 , I=− E1 − ⌬V1 r1 , ⌬Ve I=− . re 共3兲 共The signs reflect the definitions of voltage difference and of positive current flow being to the right. Thus E2 ⬎ 0 drives current to the right, E1 ⬎ 0 drives current to the left, and a higher electrolyte voltage on the right drives current to the left.兲 With these definitions the terminal voltage is given by ⌬VT = V2T − V1T = ⌬V2 + ⌬Ve − ⌬V1 =共E2 − Ir2兲 − Ire − 共E1 + Ir1兲 = E − Ir, 共4a兲 共4b兲 where r = r1 + r2 + re . 共5兲 We rewrite Eq. 共4b兲 to obtain the equation for the system as a whole, I= E − ⌬VT r . 共6兲 Note that re ⌬Ve = − Ire = − 共E − ⌬VT兲 . r 共7兲 For I ⬎ 0, the cell discharges, and the voltage across the electrolyte is opposite the emf, as can be seen in Fig. 2共a兲. As an example we take r1 = r2 = 0.01 ⍀ and re = 0.08 ⍀, so r = 0.1 ⍀; in this case the electrolyte dominates the internal 219 Am. J. Phys., Vol. 76, No. 3, March 2008 Fig. 2. The voltage profile for a voltaic cell. The numbers refer to voltage changes on moving across each circuit element from left to right for the model discussed in the text. 共a兲 Open circuit. 共b兲 Closed circuit with resistance R. resistance. We also take E2 = 1.4 V and E1 = −0.6 V 共the negative sign means that the reaction at electrode 1 drives current in the same direction as does electrode 2兲, so E = 2.0 V. 共A well-charged single cell of a lead-acid battery, with geometrical plate area of 100 cm3 has an emf of about 2.15 V and an internal resistance on the order of 0.01 ⍀.14兲 The similar example depicted in Fig. 9 of Ref. 6 took r1 = r2 = 0, so that the voltage drop across the electrodes was unaffected by the current flow. For an open circuit for which I = 0, Eq. 共3兲 yields ⌬Ve = −0.0 V, ⌬V2 = 1.4 V, and ⌬V1 = −0.6 V, so that ⌬VT = 1.4 − 0.0+ 0.6= 2.0 V. With an external resistor R = 0.4 ⍀, for which I = ⌬V / R holds, and the current is I = E / 共r + R兲 = 4 A. Then ⌬V = IR = 1.6 V. Moreover, ⌬Ve = −0.32 V, ⌬V2 = 1.36 V, and ⌬V1 = −0.56 V, so that ⌬VT = 1.36− 0.32 + 0.56= 1.6 V. If we compare the current-carrying closed circuit and noncurrent-carrying open circuit cases, we see that the voltage drop across the electrode-electrolyte interfaces is not the ideal value of the associated emf, but differs by an amount proportional to the current. In principle, the surface resistance can be determined by measuring the voltage difference between a given electrode and the electrolyte near that electrode, and determining its dependence on the current flow. The voltage profile for this circuit is plotted in Fig. 2 for an open and a closed circuit. The voltaic cell is to the left, and to the right is either an air gap 关Fig. 2共a兲兴 or a resistor 关Fig. 2共b兲兴. More realistic models for a voltaic cell include the fact that for large currents the current crossing an interface is a nonlinear function of the voltage difference across that interW. M. Saslow 219 face. Including this effect makes the equations much more complex and is unnecessary for small currents. III. CELL PROPERTIES DEPEND ON THE STATE OF CHARGE In a lead-acid cell the electrode-electrolyte interfaces are associated with the sulfuric acid-containing pores of lead and lead oxide.15–19 When the cell is well charged, the pores are large with a large surface area; when the cell is poorly charged, the pores are small with a small surface area. The reason for the change in pore size is that under discharge 共charge兲, chemical reactions plate lead sulfate onto the lead and lead-oxide electrode, thus decreasing 共increasing兲 the area that has become sulfated 共desulfated兲. The change in the pore size is not the dominant effect on the internal resistance, because the fractional utilization of the interface area does not decrease below 0.7–0.8 unless there is passification 共that is, under normal reverse current the area can no longer be recharged兲 by formation of sulfate crystals on the surface.20 The most important effect of discharge is to change the electrolyte resistance. We therefore take the internal resistance r to be the sum of a small and 共nearly兲 fixed part rs = r1 + r2 associated with the electrode-electrolyte interfaces and a part re that varies with the charge Q of the cell. This variation of r is not difficult to obtain. Recall that in the Drude theory of conductivity, which explains the difference between conductors and insulators, the conductivity is proportional to the carrier density n. In the present case the conductivity of the electrolyte also is proportional to n. Because the sulfuric acid is the limiting component, its density n is proportional to the charge Q of the cell, 共8兲 Q = 2en⍀, where each atom of sulfuric acid provides a net ionic charge 2e 共e from the rightward motion of H+ and e from the leftward motion of HSO−4 兲 and ⍀ is the volume of the electrolyte. Hence, because the resistance varies inversely with the conductivity, we have re = r0Q0 / Q, where the initial electrolyte resistance and charge are r0 and Q0. Then r = rs + r0 Q0 , Q rs = r1 + r2 . 共9兲 We repeat that voltaic cells are not really ohmic devices, and that the electrode-electrolyte interface resistance depends nonlinearly on the voltage difference between the electrode and electrolyte.15–20 In addition, both the electrolyte density and the active electrode area require treatment as continua 共that is, they depend on position兲, especially for high rates of discharge, where ionic motion in the bulk may not be able to keep up with the needs of the chemical reactions at the interfaces.15–20 We neglect such niceties here to obtain a model that is manageable and contains the basic elements to explain how batteries discharge. IV. INCREASE OF ELECTRODE RESISTANCE WITH DISCHARGE The charge of a cell decreases in proportion to its integrated discharge: 220 Am. J. Phys., Vol. 76, No. 3, March 2008 dQ = − I. dt 共10兲 Equation 共10兲 relates the current I to the rate of change of the matter in the cell, expressed in units of charge. It incorporates the ideas implicit in Faraday’s law of electrolysis. Equation 共10兲 explicitly assumes that the discharge rate is sufficiently slow that concentration-driven diffusion and electric field-driven drift can maintain the ionic densities to be nearly uniform within the electrolyte. For high discharge rates, this assumption fails. A. Discharge through a fixed load RL We now connect an external load resistor RL to the cell. With no other source of emf in the circuit, the cell produces a current through the load given by I= ⌬VT . RL 共11兲 Equations 共6兲 and 共11兲 lead to I = E / 共r + RL兲. We use Eq. 共9兲 to rewrite Eq. 共11兲 as I= E r + RL = E Q , R Q + Q0r0/R R ⬅ RL + rs . 共12兲 The quantity r0 / R must be small for a voltaic cell to be effective in driving a load for a significant amount of time. The combination of Eqs. 共10兲 and 共12兲 yields E Q/Q0 Q dQ Q0 =− , =− dt R Q + Q0r0/R Q/Q0 + r0/R 共13兲 with = RQ0 / E. Here is the characteristic discharge time for a circuit of emf E, charge Q0, and resistance R. Equation 共13兲 has the properties that for a well-charged cell, where Q / Q0 Ⰷ r0 / R, the decay is linear in time, whereas when the cell has become depleted, so Q / Q0 Ⰶ r0 / R, the decay is exponential. Equation 共13兲 can be solved numerically to find Q / Q0 as a function of t / . It can also be solved analytically, leading to mixed linear and logarithmic behavior: 冉 冊 Q r0 Q t =1− + ln , Q0 R Q0 共14兲 which can be used to find Q / Q0 as a function of t / . The dimensionless terminal voltage is given by ⌫⬅ Q/Q0 ⌬VT RL , = E R Q/Q0 + r0/R 共15兲 where RL / R is slightly smaller than unity. Comparison with Eq. 共13兲 shows that ⌫ is proportional to dQ / dt. We expect that for short times ⌫ has a downward curvature as it approaches the regime where the cell becomes ineffective, and that for times long enough that the cell has become useless ⌫ has a positive curvature. Therefore, the time at which d2⌫ / dt2 = 0 indicates the crossover in behavior. We thus consider Q/Q0 1 d共Q/Q0兲 d⌫ RL d RL = = dt R dt Q/Q0 + r0/R R 共Q/Q0 + r0/R兲2 dt 共16兲 W. M. Saslow 220 Fig. 3. The normalized charge Q / Q0 versus the normalized time t / = tE / RQ0 for R / r0 = 1 , 10, 100. See Eq. 共13兲. Legend: R / r0 = 1 共dot-dashed line兲, R / r0 = 10 共dashed line兲, R / r0 = 100 共solid line兲. Q/Q0 1 RL =− R 共Q/Q0 + r0/R兲3 共17兲 Fig. 5. The normalized terminal voltage ⌫ = ⌬VT / E versus the normalized discharge 共1 − Q / Q0兲 for R / r0 = 1 , 10, 100 and RL / R = 0.95. See Eq. 共20兲. The legend is the same as in Fig. 3. and d2⌫ 1 RLr0 共Q/Q0兲共r0/R − 2Q/Q0兲 = . dt2 2 R2 共Q/Q0 + r0/R兲5 共18兲 Thus the curvature is zero for Q = Qc, where QcR = Q0r0 / 2. Alternatively, note that Q / Q0 = ⌫共r0 / R兲 / 共RL / R − ⌫兲 and Q / Q0 + r0 / R = 共r0 / R兲 / 共R / RL − ⌫兲, which leads to 1 R2 d⌫ ⌫共RL/R − ⌫兲2 . =− dt R Lr 0 共19兲 Equation 共19兲 can be solved numerically to give ⌫共t兲. In this case it is helpful to use ⌫0 = RL / 共R + r0兲, which for the relevant case of large R / r0 is slightly less than RL / R. To find Q / Q0 in terms of t / we need to specify only the parameter R / r0. For ⌫共t兲 we must specify the parameters R / r0 and RL / R. For R / r0 = 1, 10, 100 and RL / R = 0.95 we show Q / Q0 and ⌫ = ⌬VT / E as functions of t / in Figs. 3 and 4. Note the nearly linear decrease of Q共t兲 / Q0 to zero for small t / , especially for R / r0 = 100 共initially well-charged cell兲, and the exponential behavior for large t / , especially for R / r0 = 1 共initially poorly charged cell兲. Also note the rapid falloff of ⌫共t兲 for t ⬇ . For larger R / r0, Q共t兲 decreases linearly until it reaches the abscissa, and ⌫共t兲 has an even sharper falloff. B. Terminal voltage versus discharge Battery properties are often considered as a function of discharge.10 Thus we consider the normalized terminal voltage ⌫ as a function of the amount of discharge 1 − Q / Q0. This quantity is initially zero and is unity at full discharge. To obtain it we rewrite Eq. 共15兲 as RL ⌫= R 冉 冊 冉 冊 1− 1− Q Q0 r0 Q 1+ − 1− R Q0 共20兲 . We plot ⌫ as a function of 共1 − Q / Q0兲 in Fig. 5 for the same values of R / r0 as in Fig. 4. It is implicit that RL is constant and that there is no other source of emf. C. Constant current discharge We also consider the case of constant current discharge I = I0. This situation can be produced by applying a variable 共forward兲 emf Ev that compensates for the increased resistance as the cell discharges. Its value is immaterial for our purposes. In this case Q = Q0 − I0t by Eq. 共10兲, so that it is convenient to write ⌫= 冉 冊 ⌬VT Q0 I0 =1− rs + r0 . E E Q 共21兲 If we fix I to the initial current for a given R / r0, we have from Eq. 共12兲 Fig. 4. The normalized terminal voltage ⌫ = ⌬VT / E versus the normalized time t / = tE / RQ0 for R / r0 = 1 , 10, 100 and RL / R = 0.95. See Eq. 共19兲. The legend is the same as in Fig. 3. 221 Am. J. Phys., Vol. 76, No. 3, March 2008 1 I0 = . E R + r0 共22兲 Equation 共22兲 permits us to rewrite Eq. 共21兲 as W. M. Saslow 221 thought to be lithium cells, given their non-heavy-metal nature, their high energy density 共from lithium’s high energy chemical bond—and therefore high emf—and from its low mass density兲, and the possibility that they may have a useful lifetime up to fifteen years. Despite the fact that this model has the lead-acid cell in mind, the principles we have discussed should apply to other types of voltaic cells, although the details will differ. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Fig. 6. Normalized terminal voltage ⌫ = ⌬VT / E versus normalized time t / = tE / RQ0 for R / r0 = 1, 10, 100 and RL / R = 0.95 for constant current. See Eqs. 共23兲 and 共24兲. The legend is the same as in Fig. 3. 冉 冊 1 Q0 ⌫=1− rs + r0 , R + r0 Q where 冋 Q = Q0 1 − 册 R t . R + r0 a兲 共23兲 共24兲 Equation 共23兲 is plotted as a function of t / in Fig. 6 for the same values as in Fig. 4. Note the similarity to Fig. 5, although the corresponding curves are not identical. V. DISCUSSION The model has the same qualitative behavior that we expect for a voltaic cell discharging through a fixed load resistor or discharging at constant current. There is a linear fall in the terminal voltage until the cell is nearly discharged, beyond which the terminal voltage drops exponentially. The model is not expected to be quantitative because it does not incorporate a number of important properties: 共1兲 the ion densities in the electrolyte 共and even in the electrode兲 are nonuniform, which is especially important for high currents when the ions in the volume cannot keep up with the demands of the reactions at the electrode-electrolyte interface, 共2兲 the relations between current and voltage drop across the electrode-electrolyte interfaces are nonlinear, and 共3兲 the electrode resistances are not fixed, but must be treated using a porosity 共characterized by a surface area per unit volume of the order of an inverse pore radius兲, which depends on the amount of discharge.17,18 Nevertheless, the model gives the reasonable qualitative result that for short times the current and terminal voltage fall linearly until the active area becomes so small that its resistance dominates that of the rest of the system, in which case the decay becomes exponential. This behavior is in qualitative agreement with I共t兲 data on how voltaic cells discharge.21 Our considerations have in mind the lead-acid cell, which is normally used to start internal combustion engines for automobiles. From the point of view of electric-powered and hybrid combustion-electric automobiles, the lead-acid cell has been superseded by Ni-metal hydride cells. The future is 222 Am. J. Phys., Vol. 76, No. 3, March 2008 The author would like to acknowledge the referees for their thoughtful and stimulating comments. Venkat Srinivasan was an invaluable source of information about real lead-acid batteries. Art Belmonte generously provided assistance with the figures. Konstantine Romanov provided useful comments. The author also would like to acknowledge the general support of the Department of Energy through Grant No. DE-FG02-06ER46278. Electronic mail: wsaslow@tamu.edu D. Halliday, R. Resnick, and K. S. Krane, Physics 共Wiley, New York, 1992兲, Vol. 2, 4th ed., Figs. 3 and 4, pp. 719–720. 2 H. D. Young and R. D. Freedman, University Physics 共Addison–Wesley, San Francisco, 2004兲, Vol. 2, 11th ed., Fig. 25.20, p. 961. 3 R. A. Serway and J. W. Jewett, Principles of Physics 共Harcourt, Fort Worth, 2002兲, Vol. 2, 3rd ed., Fig. 21.13, p. 775. 4 O. Blackwood, General Physics 共Wiley, New York, 1943兲, Fig. 5, p. 469. 5 O. M. Stewart, Physics: A Textbook for Colleges 共Ginn and Co., Boston, 1924兲, Figs. 270 and 271, pp. 472–473. 6 W. M. Saslow, “Voltaic cells for physicists: Two surface pumps and an internal resistance,” Am. J. Phys. 67, 574–583 共1999兲. 7 E. M. Purcell, Electricity and Magnetism, Berkeley Physics Course 共McGraw–Hill, New York, 1965兲, Vol. 2, Figs. 4.16–4.19, pp. 136–137. A similar discussion does not appear in the 2nd edition. Figures 4.18 and 4.19 of the 1st edition, which give the voltage profiles for open-circuit and current-drawing circuits with the Weston cell, are not discussed in the text. Similar figures appear in textbooks of the early 1900s; these figures may represent what Purcell was exposed to as a student. 8 W. M. Scott, The Physics of Electricity and Magnetism 共Wiley, New York, 1966兲, 2nd ed., Fig. 5.5, pp. 211–213. The text gives no discussion of the electrode emfs or internal resistance. 9 W. M. Saslow, Electricity, Magnetism, and Light 共Academic/Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2002兲, Figs. 7.20 and 7.21, pp. 314–315. 10 V. Srinivasan 共private communication兲. 11 Properly, E = E0 + 共kBT / e兲ln共关HSO−4 兴关H+兴兲, where E0 = 2.041 V, and 关HSO−4 兴 and 关H+兴 are molar concentrations of the ions in the lead-acid cell. For a six molar concentration of both ions and T = 298 K, we obtain E = 2.133 V. Reduction to one molar concentration gives the slightly different value E0 = 2.041 V. 12 If nonfaradaic discharge 共that is, ordinary, noncharge-transferring chemical reactions at the electrode-electrolyte interface兲 occurs, then even when a voltaic cell is not part of an electrical circuit, the cell can lose energy. Nonfaradaic discharge causes unused batteries to go bad. In addition, nonfaradaic discharge causes the voltage profile within the electrolyte to develop a spatially quadratic component. See W. M. Saslow, “Nonlinear voltage profiles and violation of local electroneutrality in ordinary surface reactions,” Phys. Rev. E 68, 051502-1–051502-5 共2003兲. 13 When steady-state faradaic discharge 共that is, charge-transferring chemical reactions at the electrode-electrolyte interface兲 occurs, the voltage profile within the electrolyte can develop in the steady-state a spatially quadratic component. See W. M. Saslow, “What happens when you leave the car lights on overnight: Violation of local electroneutrality in slow, steady discharge of the lead-acid cell,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 4849–4852 共1996兲. 14 See Ref. 9, Example 8.4, p. 345. 15 G. W. Vinal, Storage Batteries 共Wiley, New York, 1955兲, 4th ed. 16 J. Newman, Electrochemical Systems 共Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1973兲. 17 H. Gu, T. V. Nguyen, and R. E. White, “A mathematical model of a 1 W. M. Saslow 222 lead-acid cell,” J. Electrochem. Soc. 134, 2953–2960 共1987兲. D. M. Bernardi, H. Gu, and A. Y. Schoene, “Two-dimensional mathematical model of a lead-acid cell,” J. Electrochem. Soc. 140, 2250–2258 共1993兲. 19 H. Bode, Lead-Acid Batteries 共Wiley, New York, 1977兲. 18 20 V. Srinivasan, G. Q. Wang, and C. Y. Wang, “Mathematical modeling of current-interrupt and pulse operation of valve-regulated lead acid cells,” J. Electrochem. Soc. 150, A316–A325 共2003兲. 21 David Linden, Handbook of Batteries 共McGraw-Hill, New York, 1995兲, 2nd ed. See, for example, Figs. 3.6, 24.17 and 24.27. Wheatstone’s Concertina. Sir Charles Wheatstone 共1802–1875兲 started his research career with work on musical acoustics. In the 1820s he went into business with his brother William as a publisher of music; later the business described itself as “Inventors and Patentees of the concertina & manufacturers of harmoniums, music sellers & concertina makers.” In 1829 he patented the concertina. This instrument differs from the more familiar accordion by the use of studs instead of keys to blow air from the bellows over the reeds. This example is in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution, catalogue number 323,481. 共Photograph and Notes by Thomas B. Greenslade, Jr., Kenyon College兲 223 Am. J. Phys., Vol. 76, No. 3, March 2008 W. M. Saslow 223