Human Trafficking in Germany

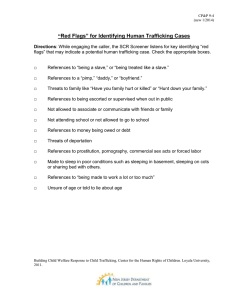

advertisement