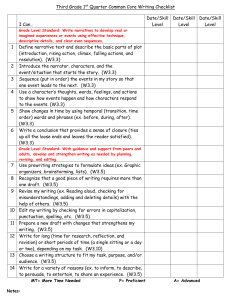

checking for understanding

advertisement