Tri–Service Armed Forces Bill

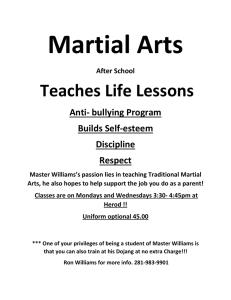

advertisement