A handbook for executive leadership of research development

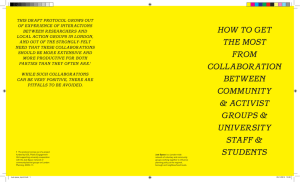

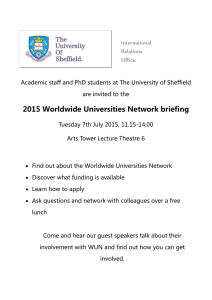

advertisement