“give us free”: addressing racial disparities in bail determinations

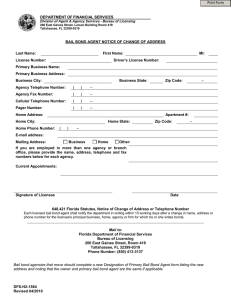

advertisement