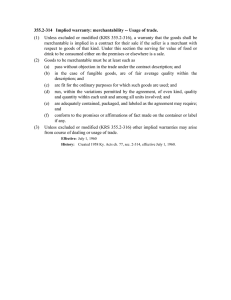

Unconscionability and Article 2 Implied Warranty Disclaimers

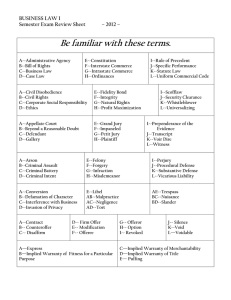

advertisement