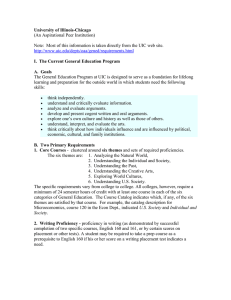

UIC Office of the Vice Provost for Faculty Affairs

advertisement