The Making of a New Copyright Lockean

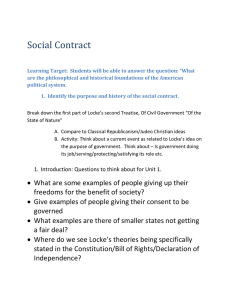

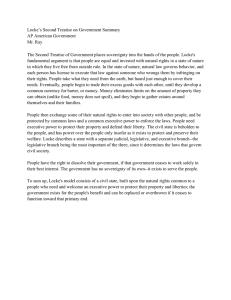

advertisement