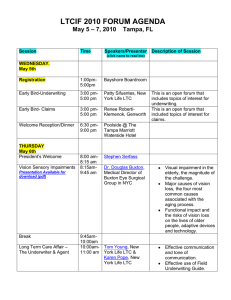

Initial Recommendations to Improve the Financing of Long

advertisement