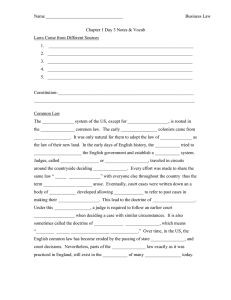

filling the gaps - Courts of New Zealand

advertisement