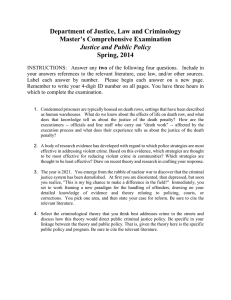

Risk Profiles, Trajectories and Intervention Points for Serious and

advertisement