view file

advertisement

835

The CanadianM irc ralogist

Vol. 33,pp. 835-848(1995)

TOURMALINE

IN GRANITICPEGMATITES

ROCKS,

AND THEIRGOUNTRY

FREGENEDA

AREA,SALAMANCA.SPAIN

ENCARNACI6N ROpa, ALFONSO PESQIIERA ANDFRANCISCOVELASCO

y Petrolagfa,Universidad

Departamento

d.eMineralagta

Aptdo,644,848080,Bilbao,Spain

delPatsVascolEHU,

ABSTRACT

In the northwestempart of the province of Salamanca(Spain),many Li-, Sn-bearingand barrengranitic pegmatitesoccur.

Thesebodiesdisplay a zonal distribution northwardfrom the Lumbralesgranite,with a degreeof evolution increasingwith

distancefrom the granite contact.Tourmaline appearsas an accessorymineral in the barren pegmatites,as well as in their

country rock In both cases,the tourmalinebelongsto the schorl-dravitesolid-solutionseries.Tourmalineshowstexfiral and

conpositional variations in relation with pegmatitetype. Subhedralto euhedralprismatic, very fine- to medium-grained

(<6 mm - 10 cn), zonedgrains are most common.In the country rock, tourmalineapp€anas prismatic-euhedral,very finegrained(<6 mm) crystals.Their Fe/lVIgvalue cha:rgesconsiderablyamongthe different pegmatitetype.s,providing insigbt into

the degreeof evolutionof the associatedpegmarites:thoserichestin Fe andpoorestin Mg areassociatedvrith the mostevolved

bodies.Tourmalinefrom the countryrocks showscompositionalcharacteristicsinheritedfrom the host schists:similarity ofthe

shapeofthe REE parerns for tourmalineand the schists,and a high contentin Cr, I{f, Th and U.

Keyword*: tourmaline,granitic pegmatite,schorl-dravite,Fregeneda"Spain.

Sotvfttens

Dansle secteurnord-ouestde la provincede Salamanca,en Espagne,setrouventplu$ieursmassifsde granit€p€gmatitique,

soit lithinifdres, stannifbresou st6riles.Cesdiff6rentsfacidssontdispos6sd'unefagonzonairei partir du granitede Lumbrales

vers le nord et monhent un degr6d'6volutionprogressivementplus avanc6en s'6loignantdu contact.La tourmaline est un

min6ral accessoiredansles pegmatitesst6riles,de m6mequedansles rochesencaissantes.

Densles deuxcas,la tourmalinefait

partie de la s6rieschorl-dravite.l,a tourmalinemontre desdiff6rencestexturaleset chimiquesselonle facibsde la pegmatite.

lrs prismessubidiomorphesi idiomorphes,i granulom6frietrbs fine ou moyenne(<6 -- - 10 cm) et zon6ssont les plus

courants.Dans les rochesencaissantes,

la tourmaline est prismatiqueet idiomorphe,et possbdeune granulomdhietrbs fine

(<6 mm). Ia valeurFe/Mg varie consid6rablement

d'un facibsi I'autre,de fagonh indiquerle degr6d'6volutionde la pegmatite

h6te. l,a tourmalinela plus riche en Fe et la plus pauwe en Mg estassocideavecla pegmatitela plus 6volude,Ia composition

de la tourmaline des roches h6tes reprend les traits compositionnelsde celles-ci, par exemple une ressemblancedans

I'enrichissement

relatif desterresrareset une teneur6lev6een Cr, I{f, Th et U.

(Iraduit par la R6daction)

Mots-cl6s:toummline,pegmatitegranitique,schorl-dravite,Fregeneda"

Espagne.

INTRoDUciloN

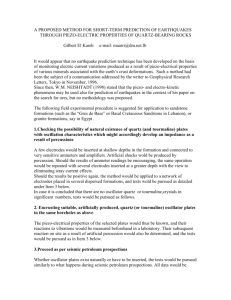

In the Fregenedaaxeaof Spain, different types of

granitic pegmatitescan be establishedon the grounds

of mineralogical and geological criteria and spatial

disnibution arcundthe Lumbralesgranite(Fig. 1). The

most commontype correspondsto simple pegmatites

without internal zonation. Zoned, Li-bearing

pegmatitesalso are relatively coulmon, as are pegmatitic veins containing quartz, muscovite,feldspars,

and cassiterite.Tourmalineappearsas an accessoryor

major mineral in many of thesepegmatites,and it is

also common in the country rock, near the contacts

with pegmatitebodies.

The compositionof the tourrnalinereflects the bulk

chemisty of the systemin which it forms, and some

studies have establishedits value as a petrogenetic

indicator(e.9.,Sheareret al.1984, Henry & Guidotti

1985, Jolliff et al. L986, Kassoli-Foumaraki 1990,

Pirajno & Smithies 1992, Kassoli-Fournaraki&

Michailidis 1994. Michailidis & Kassoli-Foummaki

1994, Hellingwetf et al. 1994). In this study, petrographicandchemicaldataon representativesamplesof

tourmaline selected from the various groups of

pegmatitesin the Fregenedaareaand their extensively

tourmalinized county-rock are given. The chemical

yariationsare discussedin order to determinewhethfr

thesedifferent types of pegmatitel) are relatedby a

836

TI{E CANADIAN MINERALOGIST

PORTUGAL

N

A

0

Duero !$1{

1Kn

TT

(f) a

(2) tr

(3) O

(4) I

(9 A

(O

(4 a

(8) o

slnxpleintraCraniticpep.

qpa&+afilalusitecodomable dykes

simpledyke.sandapophyses

sinplscodomablepoeltr

K-fetdspardiscodandykes

siEplediscorda$psgpr,

U-beadngdtscorderpeg4.

Sn-bearing<liscordantpegs.

+ + + ++ + + + + + + + + + + + + .

+++*++++++++++++++'

+++ti++++++++++++++'

+{'+++++++++++++++

+#+++++++++++++++.

eiinit'e'I i I:

if, iSau'cdtlle

+ + + + ++ .

+ + ++ + + + +

+++++++++++++*

++++++++++++++,

+++++++++++++++'

+++++++++++++++.

+++++++++++++.

ts+++++++++++++.

++++++++++|\+++.

++{L+A+

+++

+

++

Ar

^dp***

+++++++

+++.f+++++

+++++++++++

+++++++++

+++++++++++

+ + + + * + + + ++ +

Fn

++++++++++++++++++++

+ . f+ + * + + + + f + + + + + + + + + + + + .

+++++

++++++++++++++++++++++.

.+++++

+ + + + + * +x t+ + + + + a\' \s|.l.irlt + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + '

V + + + + + + + :F++ + + + + +\4l + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + +'

+.7++

+ + +a+t"+-l

*+++++++

++++++

++

ii IIIIIIii :

crl'lte,:

t I i+ I+ i+I+i+I+i+l+I+I+I+i +I +I +I +i +l!,rrlPlq

+++r++++++++++++++++++++'

B,LBiotiteisograd

E

ar. Andalusileisograd .o

sJ. Si[imanite isograd

Schist-Metagraywacke-Complex

Fracturecontainingquartzsegregations

Ftc. 1. Distribution ofthe pegmatitegroupsrecognizedin the Fregenedaarea The pegmatitetypesarelabeledas in Table l.

commonpath of fractionation,and2) arerelatedto the

nearbyLumbralesgranite.

Gsot,octcAr,Srrrwc

The pegmatitesof the Fregenedaareaappearin the

HespericMassif, in tbe westernpart of a trarrowmetamorphicbelt, with an E-W strike.This belt, situatedin

northwesternSalamanca,is borderedby the Lumbrales

pluton to the south,and by the Saucellepluton to the

northeast(Fig. 1). Both granites and pegmatitesare

intrusive into pre-Ordovician metasedimentsof the

Schist-MetagraywackeComplex. In this area, this

Complex comprises a sequenceof quartzites,graywackes,schistsand pelites, with abundantfhin hysrs

of calcsilicate. These materials have undergonetwo

main phasesof Hercyniandeformation,with the later

event of lower intensity (Martfnez Fem{adez L974).

The earlierphasegaverise to a regionalmetamorphism

that in the Fregenedaarea shows a distribution of

isograds parallel to the Lumbrales granite, locally

lsnshing the sillimanite zone,whereasthe biotite zone

is the most extensive (Frg. 1). The regional metamorphism,of mediumfe high grade,and interrnediate

pressures,determinedby the sillimanite - K-feldspar

isograd, led to incipient partial melting of the metasedimentary units at approximately 650'C and

3.5 kbars, coinciding, in general,with the appearance

of cordierite- K-feldsparin the migmatitic leucosome

(GarciaLuis 1991). The episodeof regional metamorphism precededthe secondphase of Hercynian

deformation(Carnicero1982),and it is superimposed

by a contact metamorphismthat may be due to the

presenceof a hidden granitic pluton, which has been

detectedat depthby clrilling Q.6pezPlazaet al. L982).

One of the mdn characteristicsof this area is the

greatdiversity of granitesthat outcropthere.The most

common group is that of the peraluminousleucogranites,to which the Lumbralesand Saucelleplutons

belong @g. 1). The former is part of the MedaPenedono-Lumbralesgranitic complex (Bea et al.

1988), and consists of a parautochthonous,heterogeneous,fine- to medium-grainedtwo-mica granite

(Carnicero1981).With regardto the Hercyniandeformation, this pluton is included in the group of

syntectonicmassifsthat havebeen deformedduring a

third phaseof HercyniandeformationQ-6pezPlaza&

Carnicero 1988, I-6pez Plaza & Martlnez Catal{r

1988),with a Rb-Sr isochron age of 284 t 8 Ma

(Garcia Gan6n & Locutura 1981). In spite of its

837

TOURMALINE IN GRANITIC PEGMATITES.SPAIN

(t)

2

6

Fi

<;I

z

.R

frl

M

t<

v)

.S^'

V

tll

E

EI

&

F

F

7

z

EErEsafiE*rEa

tsE$

z6

a

H.

z{,_,

S6-

E

o

HEE

Be .e E o i

E

B"

'Ept

o

_eR6 eY

d

"

*$€5€Egf,

€*sEg

EU*

E*EI

EE

E+g

o

FI

oF.

FI(J

?

.. E

-t r

sE

€esEEfi

EqE:

E€

EE: EE.E

T; EE; Eq$ rqtE,

HT;!n E*i

ETn EsE

€t

>e

o

(.td

)a)

!J€

3

il

(a

trl

,€.$g€f

€Uc

llll

F

F

u)

q-

Y<

NH

zil

b<

C)

Fr

F

g

HV

gE

€

FI

lrl

N

ts

.A:

$gcA€eEgg€€e

.s;€g$

,gE.'

EiE*E

E$a

.A

zt{

sq !i" 'B

d'o

.a-*

zo

g

x

L.

Ir

A

-i^

M

OP

trF

nit)

'E

E

E

E.AE

FE-

.Eu € tr € I

€

Fg

g=

E

*.

.h€

F'

F

U)

o

F

F

u)

Fl

F

CJ

ga

gE€

g

$x€H#r€

B

E6*

345

=F

&

o

vg

.oE e

xtn

ox

.rlN

c)

ep

&

>n

C)

z

F

a.BF

€5q

o 3.:

{

g

gg

€Ea

€€s

sag

aEg€

ce€ca

tfiE

EaCB

S9ot

o-.

h

.j

z

F

.F

'-

E

}i

F

c,

trF

do

>€

s,E

s€gEg

sE3€fl a$sE

sfls€sEE

o *'E o F.B.,

THE CANADIAN MINERALOGIST

evident petrological continuity, the Lumbralespluton

showsa cleartectoniccontol westward,whereasto the

east the deformationdecreases,and the emplacement

ofthe graniteseemsto havebeenfree ofexternal sffess

(Gonzalo Conal 1981, L6pez Plaza et al. 1982).

Another characteristicof this body is the presenceof a

migmatitic facies in the border as well as in the inner

zones,mainly to the eastofthe Fregenedaarea.As is

the casefor the Lumbralespluton, the Saucellepluton

is a peraluminous,fine-grained,two-mica granite,and

it belongsto the group of syntectonicmassifsthat were

deformedduring the third phaseof Hercynian deformation (L6pez Plaza & Camicero 1988).With regard

to their degree of rare-element enrichmsfi, ftsy

contain170-230ppm Li, 343 ppm Rb and218 ppm Ba

(Garcfa Gam6n & Locutura 1981, Bea & Ugidos

1976).The high contentsin Li andRb arenoreworthy,

as are the low contentsof Ba in both series.The K/Rb

ratioalsois low, with valuesbelow 160@ea1976,Bea

& Ugidos 1976), characteristicof granitic pegmatite

andhigtrly differentiatedgranites(Ahrenset al. L952).

PecMArnETVpEs

On the basisof mineralogy,morphology,and internal structure, several groups of granitic pegmatites

have beenrecognized.Thesegroups display a degree

of differentiation that increases awav from the

Lumbrales granite. With increasing distance from

the contact the groupsare @oda et al. 1991,Roda &

Pesquera,

inpress)(Fig. I, Table 1):

(1) Infagranitic bodies of pegmatite consisting of

quartz, K-feldspar (-icrocline and orthoclase),

muscovite,albite and schorl;thesebodiesare relatively abundantin the borderzonesofLumbrales pluton.

(2) Dykes composedmainly of quartz, andalusiteand

minor muscovite, schorl and K-feldspar (microcline

and orthoclase),of pegmatitic grain-size. They are

concordantto the coun!ry-rockfabric, showingrelated

deformation,witl a boudinagesfiucture.Thesebodies

appearin the andalusite--cordierite

zone, close to the

Lumbralesgranite.

(3) Dykes and apophyses showing aplitic and

pegmatitic facies, consisting of quartz, K-feldspar

(microcline and orthoclase), muscovite sad minel

albite, schorl, and biotite. Their grain size changes

abruptlyfrom an aplitic to a pegmatiticfacies,andtheir

shapesvary geatly. Thesebodies are localed to the

southeastof the area studie4 near the Lumbrates

granite,associatedwith the sillimanite, andalusite,and

biotite zones.

(4) Conformablebodiesof pegmatiteof narrow width

(<1.5 m), locally showing internal zoning. They are

composedmainly of quartz, muscovite, K-feldspar

(microcline and orthoclase),schorl, albite, and minor

andalusite,chlorite, game! and biotite. Host rocks

commonly display strong tourmalinization near

the contacts.These bodies are located close to ttre

Lumbrales granite. They are associaledmainly with

the andalusitezone and to a lesser extent with the

sillimanite andbiotite zones.

(5) Pegmatitebo'diesmainly composedof K-feldspar

(microcline and orthoclase).Other phasesthat may be

present are quartz, muscovite and pyrile. They are

discordant to the country rock, appearingnear the

contact with the Lumbrales granite, associatedwith

the biotite zone.

(6) Discordantbodiesof pegmatitethal in somecases,

show a layered internal structure. They consist of

quartz, K-feldspar (microcline and orthoclase),

muscovile,and albiie. In the bodies farthestfrom the

Lumbralesgranite, amblgonite may appear,whereas

close to the granite, phosphatesof Fe-Mn t Li are

common, as well as tourmaline as an accessory

mineral. Moreover.the host rock can show a variable

degreeof tourmalinization.Situatedin an areabetween

I and4 km to the north of the Lumbralespluton, group

6 is the most abundant.The host rocks exhibit lowgrade regional metamorphism(biotite and cblorite

zones).

(7) Discordant bodies of Li-mica-bearing pegmatite.

Thesebodiesusually displaya zonedinternalstructure.

They are composedof quartz,Li-bearing mica, albfte,

K-feldspar(microcline and orthoclase),muscoviteand

minor amblygonite, spodumene,cassiterite, apatite,

and columbite-tantalite. f6urmaline has not been

found in thesepegmatites,althoughtourmalinizationis

variably developedaroundthepegmatites.Thesedykes

crop out along a narow ban4 4 6 km north of the

Lumbrales granite. As is the case with the previous

ca0egory,thesebodiesof pegmatiteareassociatedwith

the biotile aud chlorite zones.

(8) Bodiesof pegmatiteconsist"rg of quartzand minor

fine-grained muscovite, albite, microcline and

cassiterile. Their county rock exhibits a variable

degreeof tourmalinization;as in the previous group,

tourmalinehas not beenfound as a constifirentofthe

pegmatites. These dykes locally show internal

zonation, being folded, with the axial plane neady

horizontal.They appearin the norflem zoneofthe area

studie4 being cut by some bodies of the previous

category. These dykes are only associa0edwith the

chlorite zone.

PsrRocRAPnY

Textural and parageneticdifferences among the

tourmaline samples from the various fypes of

pegmatilehavebeenobserved(Table 2). Threemodes

of occurrencecan be established.The first one is a

medium to very fine-grained (5 cm - <6 -m),

prismatic tourmaline, that appears homogeneously

distributed in the intragranitic pegmatites(1), in the

quartz-andalusitedykes(2) nd in the apophyseswith

aplitic and pegmatiticfacies (3). Commonly,this type

of tourmalinegrowswith quarczin the corezonein the

839

SPAIN

TOI]RMALINE

IN GRANITICPEGMATITES.

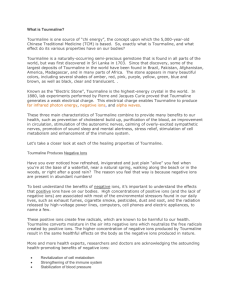

TABLE 2. TOURMALINE DISTRIBUTION IN TIIE FRECENEDAPEGMATTTES

AND TI]EIR TOTIRMAUNTZEDCOI.INTRY-ROCI(

TEXTURE GRAIN SIZE'I

PEGM.TOURMAL.OCCURRENCE MINBNAL ASSOCIATION

TYPE'

TYPE

1

mainly in the

intEmediate

z&e

qu8%K-Feldspfr,

albite, muscovie

sub-oeuhedral

prismatic, aned

gains

fiIEto

medium

quar%K-Ibldspar,albib'

muscovite,Fe-Mn pho

$tbh€dral

veryfine

qutr%andalusiB,

muscovir,K-Feldspar

ohedral,stender,

pdsmaticgrains

veryfine

lofrne

I

withln the

pegmatitos

I

2

widfn &s

dYftes

|

wittrintheapttic

$aE,K-Foldspar,mu8covile,

albite,biotilo

aDdpegnalildbodi€s

qomz,K-f€bspar,mucovite,

wfthinrheaplit'rc

albfue,biotie

annpegmatitiiUaies

mainly in

thecdg zone

ln rhoaplitic facies

ofsonepogmadt€s

comtsyrock

I

nainly in tle nall

zoeandaplitic&cies

of somep€gmatites

euMnl

srbbedral

interstithl

fineto

medirm

fire

ouaft,. K-FeldsDd.alhire, sub-to qhedral

*osco"ie,ao-Oatusite, prismaticgrEins

garn€f,apatite

fine to

medium

quar%K-Rldspq,albiq

muscovir,biotiE

veryfine

t()fine

an-to$bhedral

intsstitid

muscovitc,biolits,quaar piscratic+uhe&al veryfino

K-Fel&p,a,albie

qrlartz,albilx K-Feldspr,

musc.oviio,

Fe-ft{ni:Li phosphatss

sibhednl

firc !o

mediutrl

colnttryrock

muscovite,biotib,quartz, Eisnaticeohedral vayfine

K-Feldspd,albiF

7

3

comtsyrcck

muscovite,biotite,quaft4 pisnatic+uhedral veryfine

K-Fsp,albite

8

3

courtsyrak

muscovite,biotib,quafiz, pinnadccuMral

K-Fsp,albitB

veryfine

r numberof lhe pegmatiterypesasin Table l; ttgrain size:v€ry fine =< 6 mm; frne= 6 mm to 2'5 cm;

medlum= 2"5 cm to 10 cm.

simple conformablepegmatites(4); less commonly,

the crystals are perpendiculaxto the contactwith the

cormtry rock in the border zones of the simple

discordant pegmatites (6). This type of tourmaline

usually showsan internal concentriczonation,with a

variable, occasionally intense pleochroism" ranging

from yellow to brown-orangein the border zones,and

from bluish greento blue or colorlessnearthg core of

the prism"

The secondtype of tourmalineis interstitial andfine

to very fine grained(2 cm - <6 --). It occursin the

apophyseswith aplitic andpegmatiticfacies(3) andin

the simpleconformablepegmatites(4). Generally,this

type of tourmalineshowsa pleochroismranging from

yellow to brown-orange.

The third type is very fine grained(<6 mm) and is

found in the countryrock, at somepegmatite- county

rock contacts. Crystals are euhedral and show a

variablepleochroism,ranglngfrom brown to greenish

yellow in the border zonesand from bluish green to

deepblue in the inner zones.

Dera CoLLesfloNANDANALYS$

The tourmalinesamplesstudiedhave beenselected

from the mostrepresentativebodiesof pegmatiteof the

area,as weUas from their tourmalinizedcountry-rock

Tourmalinecrystalsftom at leastfour different bodies

of each type of pegpatite have been analyzed.The

sampleswere preparedby magnetic separationand

840

TIIE CANADIAN

MINERAIOGIST

Frc. 2. FeO in tourmaline measuredby electronmicroprobe

ansneutron-activationanalysis.The latter methodshows

the "boron shielding effect" (King et al. 1988), and the

results so obtainedare between24 and 49Volower than

thoseproducedwith an electron microprobe.The traceelement concentrations were corrected bv the ratio

Fe6a/Fepa.

O

.o

z

hand-picking,and the separateswere examinedwith a

binocular microscopeto remove contaminatedgrains.

They were ground by hand in an agate mortar and

analyzed for major elementsusing a Camebax SX

50 electron microprobe. Operating conditions were:

voltage 15 kV and beamcurrent 10 nA. Wollastonite,

conmdum,hematite,graftonite, albite, orthoclaseand

MgO were used as internal staadards.Finally, the

concentrationsof Li and Sn was determinedby atomic

absorptionspectrometry(AA); concentrationsof Sc,

Co,7n, As, Se,Rb, Sr, Mo, Ag, Cs, Ba, REE,Ta W,

I'

24681012

FeO(wr7o)by ElectronMicroprobe

TABLB 3. AVERAGE COMPOSMON OF TOURMALINE FROM TTIEDIFERENT

TYPESOF PEGMATITE AND THEIR TOURMALINZED COIINTRY-ROCX(

'Peg.type

(Tl)

{r,

(r3)

(T4)

(T4)CR

(16)

sio2

Tio2

41203

FeO

MnO

MgO

CaO

Na2O

K20

Total

9.72

0.48

33.05

1224.

0.U

1.56

0.O7

l,6l

0.05

83.95

35.47

0.90

33.99

8.42

0.05

3.&

4.49

L,49

0.04

u.49

34.67

0.40

34.11

rL03

0.13

2,45

0.09

t.75

0.M

85.67

v.99

0.58

92A

10.14

0.r1

3n

o.?A

1.68

0.05

85.30

34.98

0.40

32.47

13.82

0.12

L23

0.06

r.69

0.04

84.81

35.45

0.16

U.t3

12.89

022

0.87

0.11

1.58

0.03

85.43

(T6)CR (T7)CR (TE)CR

36.17

0.70

32:75

9.n

0,08

4.18

0.38

2.V2

0.05

8620

36.t4

0.99

31.43

9.80

0.03

s.A1

0.3r

22r

0.08

86.06

35,4

0.84

31.59

ll.0l

0.r3

3.90

a.&

2.05

0.05

85.86

481461513

Strucural fomula on thebasisof 24.5aromsof oxygeo

si

AI

AIT

5.949

6.675

0,051

5.913

6.683

0.087

5.9n, 5.841 5.985 5.973

6.753 6.739 6.549 6.719

0.r7E 0.159 0.015 0.v27

N z

6.@0

6.000

6.000

6.000

Al Y

Ti

si Y

Fe2+

Mn

Mg

Y lotal

4.624

a.62

0.000

L.7s4

O.V25

0.398

2"860

0.596

0.113

0.000

1.1?j

0.003

0.906

2396

0.575

0.050

0.000

1.689

0.018

0.613

2.946

0534

0.u72 0.051

0.000 0.@0

t.4t6

L.978

0.016 0.018

0.813 0.374

2.8n

2.894

Ca

Na

K

X total

a.al2

0.533

0.011

0.557

0.088

0.483

0.008

0.579

0.016 0.M2

0.569 0.545

0.fir

0.011

4.5v2 0.598

6.m0

0.580

0.012

0.560

0.008

0.580

s.n8

6.000

6.381 6.148

0.a2 0.m0

5.970

6240

0.030

6.M

6.000 6.000

6.000

0.751

0.020

0.000

1.816

0.032

0.217

2.837

0.359

0.086

0.000

1.3&

0.011

1.M9

2.U9

0.148

o.Lu

0.0n

1360

0.0M

r.29

2.912

0.210

0.105

0.0m

1.542

0.018

0.975

2.850

0.020

0.516

0.007

0.542

0.067

0.il9

0.011

o.1n

0.056

oiw

0.016

aJa

0.116

0.666

o.ou

w93

tpegmadtetype as in Table l; N: numberof analyseqCR: toumaline ftom the cormtryrock- All Fe is

calculaedasFeO.

841

TOURMALINE IN GRANITIC PEGMATITES.SPAIN

Th and U were determined by neufron activation

@,IAA). Trace-elementanalyseswere performed by

X-Ray AssayLabs of Don Mlls, Ontario.

According to King et aL (1988), the determination

of trace-elementandREE concentationsin tourmaline

by neufton activation is hamperedby the problem of

the incident neufron-flux suppressionin the sample,

arising from the large neufton-capturecross section

of B. This effect has been checked using the Fe

concentrationsobtained by neutron activation and

electron-microprobeanalyses(Frg. 2). The concentrations obtained by neutron activation seem to be

between 24 and 49Volower than those measuredby

electronmicroprobe.Thesedeviationscanbe corrected

with the factor Fes1alFeNa,

to permil comparisons

amongthe various samplesof tourmaline.

Tourmaline sampleswere analyzedwith an X-ray

diffractometerusing silica as the internal standardby

scanning over the interval 5-:70" 2g using CuKcx,

radiation.Unit-cell dimensionswereobtainedusingthe

progrrm of Appleman& Evans(1973).

Mnw.nal CtmvflsrRY

All of the tourmalinesamplesanalyzedbelongto the

schorl-dravileseries,mainly the Fe2+-richendmember

(Tables 3, 4, Fig. 3). Nevertheless,the data show

compositionalvariationsthat correlatewith pegmatite

type (Figs.3o4, 5,6). It is alsoremarkablethat in no

casewas a differencefound betweenthe composition

of tourmalinefrom the core and that from the wall of

the samebody of pegmatite.

ln general, tourmaline crystals from pegmatites

showhigher concenfrationsofFe andlower concentrations of Mg than those growing in the country rock

(Frg. 3). Tourmalinetaken from the simple discordant

pegmatites(6) has the highestFe/IVIgvalue, whereas

tourmalinefrom the quartzand andalusitedykesshow

the lowest Fe/Mg value (Fig. 3a). Among samplesof

tourrnalinetakenfrom the countryrock @ig. 3b), those

found in schist near bodies of Li-rich pegmatite

(7) have the lowest Fe/IvIgvalue, whereasthosefrom

the host rock of the simple concordantpegmatites

(4) shows the lowest concentrationsof Mg and the

highestconcentrationsof Fe.

The total number of cations in the Y site implies

vacancies,with a deficiency in R+ (Na++ 2C*+ + K)

and R2+ (Fe2*+ Mg2* + Mn2+) and an excess of

p3+ 14f3++ 48 Ti4\ Clable 3, Fig. 4). Thesemay be

due to the effect of two coupled substitutions@oit

& Rosenberg 1977) involvinC (1) alkali defect:

(OID- + R2+= l?3++ O2-,and (2) proton loss:l?++ R2+

= ft3+* vacancies.

In general,the (R*+RlyR3* value in the tourmaline

from the country rock is higher than that of the tourmaline from the pegmatiticbodies(Figs. 4a"b), which

reflectsthe higher Al contentsofthe latler. In contrast

to the suggestionsof Foit & Rosenberg(1977),

substitutions involving alkali deficiency zue more

common than those implying proton loss. Such

substitutionsare partly contolled by bulk chemical

environmen! H2O-rich systemsfavoring alkali-defect

substitution (Gallagher 1988). Tourmaline from

pegmatites(2), (3) and (4) shows a higher degreeof

TABLB 4. TRACE-ELEMENTCONCENTR.ATIONOF TOIJRMALINE FROM TIIE DIFFERENT

TYPESOF PEGMATITEAND THEIR TOIJRMALINZED COWTRY.ROCK

rPes. rrpe

LI

Sc

Cr

Co

ZD

AE

Se

Bb

Mo

ag

SB

Cg

sf

Ta

w

Tb

U

Ls

Ce

Nd

Sm

EE

Tb

Yb

h

La.lrYb.!

(T1)

(Tl)

(T3) (T3)

52

10.71

10

8

1700 986

4.4

4.4

<5

<5

34

25

8.5

8.5

E.5

E.5

0.5

0.4

1.7

<5

0.42

o.42

o.42

1.1

0,4

<5

0.42

0.42

r.4

6.E

0,08

0.r7

<0.85 <0.85

0,1

0.04 0.04

1.6

6.8

0.08

42

(T4)

(T4)

(T4)CR (T4)CR

(T6)

29

29

460

3

3

112

12r

1n9

4.4

<5

25

12

8.5

26

3.4

0.4

5

<5

0.85

0.42

561

5

<5

68

8.5

8.5

32

29

5

1.7

<5

10.14

1.7

351

3.4

<5

68

8.5

8.5

92

c9

4.9

<1.'1

12

10'71

2.4

0.85

3.4

6.8

0.08

1.O2

<0.85

0,1

0.04

t.2

57.8

34

15.3

4.2s

1.19

<0.85

0,5

0.15

23.0

61.2

36

20.4

+.93

1.19

<0,85

0;8

0.29

r1.2

11?3

4.4

<5

25

8.5

8.5

15

13

0.4

<1.?

<J

0.42

0.42

41.5

74.8

28.9

5.U

0.85

<0.85

0,5

0.12

31.6

0.42

3.4

6.8

0.08

0.17

<0.85

0,1

0.04

1.6

1.02 1.02

3.4

3,4

6.8

6.8

0.34 0.17

0.17 0,t7

<0.85 <0.85

0,1

o,7

0.29

0.04

0.5

3,9

45.2

E6,7

6,46

0.85

0.85

0,5

0.85

34.4

(T7)cR (T7)CR

(T6)

22

54

50

95

16564.8555.48.8

109

131

3

3

12251512141920

1581

663

1258 lO54

4.4

4.4

<3.4

4-4

<5

<5

<5

<5

34

51

25

25

8.5

8.5

8.5

8.5

8.5

8.5

8.5

8.5

96

20

12

51

8.5

3.4

3.4

0.8

2.7

5.8

0.4

0.4

s

1.7

<1.1 <1.7

<5

<5

<5

<5

17

18,1

0.42

0.42

2.9

7

1.2

0.42

valqsiappoLaq/Ybcrarioofchodrit+amlizedocdttali@*numb4oflheleg@dIiq

CR:couty-toc.k

md Sa"hwoba

wted

with theFe,g6/F411fctor'

Table 1. AUdata scel|tu

380

842

THE CANADIAN MINERALOGIST

%

s0

0.0 L

0.8

lo

o0

0.0 L

0.t

Z-1r

1.5

1.4

Fe

. M (1) simpleintraEronilic pegrn.

E @ (2)quare+andal. cofonnpegrn

c Nl €)simptedykes ardapophysos

I

El

1.6

1.4

Fe

r @ (4) simple confoun. pegn, (CR)

A @ (Osinplediscordottpegtn(CR)

a Nl

(s)simpteconform.pegm.

o !

En (O simplediscordantp,gn

O Li-dchdiscordaotpegm. (CR)

(8) Sn-richdisco'daatpegrn, (CR)

Frc. 3. Plot of concentrationof Fe versasthat of Mg in tourmalinefrom someof the different types of pegmatite(a) and their

tourmalinizedcountry-rock(CR) (b). Valuesare expressedin atomsper formula unit (numbersasin Table 1).

-N

h*'

to

62

64

66

R3+

ae-

Lo

o Ml (l)dnpleinragnrddcpegm.

tr W (2)qudlz+mdal. confonn,pgm

o E! (3)cindedy&es drd spophysss

I El (4) simplecofornr.pegm.

1 @ (6) eimplediscordartpogn.

72

uui

62

6,4

66

6.t

7.0

72

ill+

r ffil (4) sinpleconform. pogm.(CR)

A @l (6)*nplediscudatpegn (CR)

. N

o I

(DLt-ddtdbcodaatpm.

(CR)

(8)Sn-richdscordantpeen (CR)

Iric. 4. (/?++ R2+)versusR* variation in tourmalinefrom someof the different typesof pegmatite(a) and thet tourmalinized

country-rock(CR) O). The variation can be relaJedto alkatidefect and ploton-losssubstitutionsin tourmaline.The lines

representcompositionsbetween unsubstinrtedschorl-dravite and the fully substitutedend-members(proton-loss and

alkali-defectend-members).

Diagrammodified from Manning (1982) (numben in rhe legendasin Table l),

843

TOURMALINE IN GRAN]TIC PECIMATITES.SPAIN

schorl

*rf"("0s0

schorl

Alsil&soAls#'e(tot)s0

f (1)simpleinragaoiticpep.

tr (2) quartz.ilndal.conform.pegm

O (3) sinplEdykesandapophyses

pegma (4) simpleconform.

A (6) sinplediscordantpegm-

Alsd&so

(CR)

x (4)sinplecooform-pegn

a (6) siryle discordantpeep.(CR)

(CR)

a C/)U-richdicorda-otpeCn

O (8) Sn-richdiscordantpef.(CR)

Ftc. 5. Al-Fe(totFMg diagram (in molar proportions) for tourmaline from a) some of the pegmatitetype.sand b) their

tourmalinizedcountry-rock (CR), with fields after Henry & Guidotti (1985). l: Li-rich granitic pegnatites aod aplit€s,

2: Li-poor granitic rocks and associatedpegmatiresand aplite,s,3: Fe-rich quartz-tourmaline(hydrothermatlyaltered

not

granite,s),4:metapelit€sandmetapsammites

so'existingwith an Al-saturatingphase,5: metapelitesandmetapsammites

coexistingwith an Al-sannatingphase,6: Fe-rich quartz-tourmalinerocks, calc-silicaterocts, and metapelites,7: low-Ca

and metapyroxenites(numbersin the legend

meta-ultamafic and Cr,V-rich metasedimentary

rocks, and 8: metacarbonates

asin Table l).

proton-losssubstitutions,suggestingthat its development was mainly buffered by alkalis insteadof H2O.

On the contraqt, tourmaline from pegrnatites(1) and

(6) presents a greater degree of alkali-deficient

substitutions,which would indicate a higher availability of water in the system.Tourmaline from the

country rock shows a greater degreeof alkali-defect

substitutions, likewise reflecting growth of these

crystals of tourmaline in a H2O-rich environment

during metasomatismof the wallrock schist.

Nevertheless.in calculationson the basis of %L5

oxygenatoms,the relative

of "lkali-defect

A way to allow for protonsubstitutionis exaggerated.

loss substitutionis to normalizecation contentsto 6Si,

but then the degree of proton-loss substitution is

exaggerated.Normalizationsbasedon 24.5 atoms of

oxygen and to 6 atoms of Si represent extreme

positions not found in natural tourmalines(Ga[agher

1988).On the other han4 the contentof ferric iron in

the tourmaline would not changethe disftibution in

Figure 4, as accordingto Henry & Guidotti (1985),

where tourmaline compositionsplot above the line

schorHravite in the Al-Fe-Mg diagram (Fig. 5), the

amountof Fe$ is very low.

In the Al-Fe-Mg and Ca-Fe-Mg diagrams(Henry

& Guidotti 1985),most of the tourmalinesamplesplot

in field 2 (Figs. 5, 6), which correspondsto tourmaline

from Li-poor granitic rocks andtheir associatedaplites

andpegmatites,whereasthe rest of the suiteplot in the

metapeliteand metapsammitefields.

The total concentations of.REE in all tourmaline

samplesoparticularly those within the bodies of pegmatite,arelow Clable4). In termsof REE distribution,

the tourmaline of the country rock has a moderately

fractionated pattern (chondrite-normalized La./Yb

between L4,2 ard 34.4), with a monotonic decrease

from Ia to Yb, followed by an uptum to Lu; the

tourmaline taken from pegmatitic samplesshows a

highly fractionated pattern (chondrite-normalized

IalYb between 0.6 and 3.9), with a scatter of the

values.

The tourmaline from pegmatitic samplesis also

so that tourmalinefrom

poorerin otherfraceelementso

the country rock showshigher contentsin Cr, Rb, IIf,

Th and U Clable 4). It is also notable that the

tourmalinein the country rock adjacentto the Li-rich

pegmatites (7) shows a relative enrichment in Li

(38H60 ppm), Rb (68 ppm) and Cs (29-39 ppm).

Most of the tourmalineprisms are zonedconcentrically aboutthe c axis. This zoning andthe shapeof the

crystals reflect the easeof growth in the c direction

(Iolliff et al. 1986).The zoning is cbromaticandcom-

8M

TTIE CANADIAN

MINERALOGIST

(1) simpleintsaganftic pogm.

(2) quare+mdal @nfom pegm

(3) simple dyks 8d apophys€s

(4) sinpls conlom.psgm, (Ct)

I (a) simplo conbm. pegm.

A (O dmple drscordantpegm"

A (O simple discordantp€gn-(A)

a CDU-rich dicodantpess. ((})

a

lI

C

:

O (8) Sn-rich discordantpep. ((b)

\2s

a

\25

b

Mg

Ftc. 6. Ca-Fe(tot)-Mg (in molar proportions)for tourmalinefrom a) someof the peg@aritetypes and b) their tourmalinized

country-rock(CR), with fields after Henry & Guidotti (1985).1: Li-rich graniticpegmatitesandaplites,2: Li-poor granitoids

and associatedpegmatites and aplites, 3: Ca-rich metapelites,metapsammites,and calc-silicate rocks, 4: Ca-poor

metapelites,metapsammites,

and quartz-tourmalinerocks, 5: metacarbonates,

and 6: meta-ultramaficrocks (numbersin the

legendasinTable1).

positional,with a slight tendencyto enrichmentin Mg

in the core relative to the rim, observedin all groups

(Frg. 7). A relation betweencompositionand color has

not beenestablished,as there are zoneswith the same

color and different composition,whereascrystalswith

similar contents show different colorations. These

differencescould reflect small variations in the ratio

Fe2+/Iie3+,

Finally, results of the unit-cell determinationsare

listed in Table 5. Values of a versw c are plotted in

Figure 8. The tourmaline samples plot near the

schorl-dravitereferenceline @onnay&Barton 7972),

near the schorl end-member,in agreementwith the

chemicaldata.

Drscussron

The observedsom.positionalvariationsindicate the

importanceof coupledsubstitutions(alkali-defectand

proton-losssubstitutions),which aremore extensivein

lsumaline from pegmatitesthan from the country

rocks @g. 4). This variationcould be explainedby the

greateravailability of Fe and Mg in the county-rock

envtonment. Manning (1982) found that the extentof

such coupled substitutions becomes greater with

decreasingtemperature,i.e., ldrth an increasein the

degreeof fractionation. However, all the tourmaline

samplestaken from pegmatitebodies show a similar

extent of these coupled substitutionsGig. 4a); their

845

TOT]RMALINEIN GRANITIC,PEGMATITES.SPAIN

6.50

E

x

6

o

R

t 6.00

3

Es.:o

3

I

EZ@

?

tt<

q

P

Erso

E

1.25

l.@

+st

1.00

+Al(bt)

+Tl

+F9

0J0

035

+Mg

+Ca

+Na

0.00

0.9

0.25

0.m

Ftc. 7. Detailed compositionalvariation of zoned crystals of tourmaline occurring in or near a) enclosedpegnatits (1),

b) apophyseswithin aplitic andpegmatiticfacies(3), and c) simplediscordantpegmatite(6) (CR: countryrock).

extentis thusnot a usefirltool to monitor differencesin

degree of fractionation. Moreover, the tourmaline

occurringin the county rock nearsimpleconformable

pegmatiles(4) showsa gre,,tetexlent of suchsubstitutions relative to that in the schists near the simple

discordantpegmatite$(6), the Li-rich pegmatites(7),

andthe Sn-richdykes(8) (Fie. 4b). Thusodifferencesin

the conditions of crystallization, such as the rate of

crystallization and in the compositionof the original

melts, also could affect the exlent of these substitutions.

Tourmaline in the pegmatiteshas, in general, a

higher Fe/IMgvaluethanthat found in the county rock

(Fig. 3). Among the tourmaline samples from

pegmatites@ig. 3a), the richest in Fe and the poorest

in Mg occursin g[e simFle discordantpegmatit€s(6),

followed by the intragranitic pegmatites(1) and the

apophyseswith aplitic and pegmatitic facies (3).

Tourmaline from the simple comformablepegmatites

(4) showsa lower contentin Fe; finally, the richestin

Mg is that associatedto the quartz-andalusitedykes

Q). At a particular set ofpressure-temperatureconditions, the compositionalevolution of the pegmatiteforrning melt-fluid system is closely related to the

stability of a given compositionof tourmaline.Thus,

basedon ionic sizeandcharge(fauson 1965),hthiumbearing tourmaline would be expectedto be more

stable at lower temperaturesthan Fe-rich tourmaline,

which in turn will be more stable than Mg-rich

tourmaline. Previous investigators (Neiva 1974,

Manning 1982,Jolliff et al. 1986)agreewith the fact

that tourmaline associatedto the earliest stages of

differentiationis richer in Mg thanthat crystalizing in

the later stages.In addition,zonedcrystalsin our suite

tend to show a rim emiched in Fe relative to Mg,

compaxedto the core. It thus seemsthat the sequence

obtained for the Fe/I4g value in tourmaline from

pegmatitescould be used as a tool to establishthe

86

TIIE CANADIAN MINERAL@IST

TABLE 5. IJNIT.CFI I - DIMENSIONS OF

REPRESENTATIVETOURMALINE SAMPLES FROM

T}ilE PEGMATTTESOFTIIEFREGENEDA AREA AND

THEIR TOURMALINZED COI]NTRY.ROCK

Ttpo peg.* a(A)

c(A)

rs,992Q)

15,957(4)

(r2)

15,950(1)

(r3)

15,960(1)

15,956(2)

Cr3)

15,957(1)

G3)

15,961(r)

G3)

(I3)

15,971(1)

r5,959(r)

CT4)

(r4)

rs,954(1)

15,959(1)

CT4)

(r4)

15,968(1)

(r4)

15,954(1)

158s3(1)

CI4)

(r4)

r5.958(r)

04xcR) rJ,967(1)

CI?X(R') 15,955(3)

G1)

Gl)

cla

Y(43)

0,44E

7,166(l) rs87A$)

7,156(3) 1578,2(9) 0,449

7,r69(1) 1s79,7(3) 0,449

7,154(0) ts78,3(2) 0,448

7,L57(r) 1578,0(4) 0,449

7,r52(t) Ls77,3(2'., 0,448

7,r7o(2) 1582,2(5) 0.449

7,153(1) 1580,4(2) 0,448

7,r58(0) 1s79,1(2) o,449

7,r5r(1) r5?6,6(3) 0,448

?,15s(0) 1578,3(2) a.448

?,r56(1) 1580,3(4) 0,448

?,1s2(0) t576,6(2) 0,44E

0,450

7,178(r) rs82'2Q)

7,161(1)

7,rs3(0)

7.r7s(2)

GD(CR) rs,976(2' 7,t75(2)

crO(cR) 15,958(2) 7,r7s(r)

(nxcn)

7,167(2)

?,t52(L)

WXCR)

Ls79,4(3)

L579,5(2)

1582,0(6)

1586,r(5)

1582,5(4)

1s?9,8(7)

(* numbemof pegmatitcqpes as in Table I

rock) .

0,M9

0,448

0,450

0,M9

0,450

o,M9

0,448

: cotulEy

sequenceof crystallization for the pegmatitebodies.

According to this ratio, the most evolved tourmalinebearing pegmatiteswould be 66s simple discordant

pegmatites (6), followed by tlte intragranitic

pegmatites(l) and the apophyseswith aplitic and pegmatitic facies (3). Finally, d[e simple comform.able

pegmatites (4) and the quartz-andalusitedykes (2)

seemto be the leastevolvedpegmatites.This sequence

agreeswith that obtainedfrom the K/Rb ratio in micas

and K-feldspar from these pegmatites(Roda et al.

1993).In the pegmatitesofthe Fregenedaarea,therefore, tourmaline associatedwith the early stagesof

crystallizationis richer in Mg than that growing later,

which is richer in Fe.

Concentrationsof REE are uniformly lower for

tourmalinein thepegmatitescomparedtotourmalinein

the country rocks. This rnay mean that the .REE

abundancesand disfributions in tourmaline are predominantly confolled by the parageneticconditions,

that is. the REE contentin tourmalinereflects theREE

conlent of the medium where the tourrnalinecrystallized (Jolliff et al. 1987,King e/ aL 1988).Therefore,

the high concentrationsof REE n tourmalinefrom the

country roctrs may be inherited from the schists in

which they grew. This inheriunce could cause the

similarity in shapebetweenthe patternsfor tourmaline

of the county rock and thoseof the metasedimentary

rocks of the Schist-MetagraywackeComplex.

Tourrnalinefrom the country rock near the Li-rich

pegmatitesshowsevidenceof enricbmentin Li, Rb and

Cs, asa result of the interactionof a fluid derivedfrom

l9(., z.l

7.

elbaite

16.060

15.780 15.820 15.8@ 15.90015.940 15.980 16.020

"

a(A)

Ftc. 8. Unit-cell dimensionsof tourmalinesamplesrepresentativeof the different typesof

pegmatite and their tourmalinized country-rock Referencelines from Donnay &

Barton (1972),modified from Epprecht(1953).

TOTJRMALINEIN GRAMTIC PECiMATITES.SPAIN

the crystallizing melt and the country rock.

Tourmalinizationof the schistsis strongonly in a halo

approximately 20 cm vdde around these pegmatite

bodies; beyond 50 cm, tourmalinization is not

developed.

Finally, the tourmalinecompositionsplot in the field

of Li-poor granitic and associated rocks, on the

Al-Fe-Mg and Ca-Fe-Mg diagrams. Note that

the pegmatitesthat contain tourmaline are spatially

relatedto the Li-rich Lumbralesgranite,which contain

from 170to 230 ppm of U (GarcfaGa:z6n& Locutura

1981). This apparentconffadiction suggeststhat, on

one hand, the composition of tourmaline may be

influenced by the chemical environmenq achieving

mixed peffogeneticaffinities, an4 on the other hand,

the geochemicalconditionsexisting during the formation of the granite and its assosiatedpegmatitesare

complexandnot completelyunderstood.

ACKNowllDGg\dENTs

847

(1982): Estudio del metamorfismo existente en

torno al granito de Lumbrales (Salamanca). .Srvdla

Geolo gica Salmanticensia 17, 7 -20.

DoNNA! G. & BARroN,R., Jn. (1972): Refinementof the

crystal structureof elbaiteand the mechanismof tourmaMineral. Petrogr.Mitt. lE,

line solid solution. Tschermalcs

n3-286.

EppREctrr,W. (1953): Die Gifierkonstantender Tirmaline.

SchweizMineraL Petrogr. Mitt. 33, 48l-505.

Fon, F.F., JR.& Ross{BRG,P.E. (1977): Coupledsubstitutions in the tourmaline group. Contrib. Mincral. Petrol,

62.109-tn.

GALLAcIIER.,V. (1988): Coupled substitutions in

schorl-dravitetourmaline:new evidencefrom SE Ireland.

Mineral. Mag. 52, 637-650.

GARcfAGARZON,

J. & LocuruR4 J. (1981): Dataci6npor el

m6todoRb-Sr de los granitosde Lumbrales-Sobradilloy

Villar de Ciervo-PuertoSeguro.Bol. Geol.y Min- dz Esp.

9L1,68-72.

This work is part of a Ph.D. thesis,which has been

mainly supported by a grant from the Education,

Universities and Investigation Deparment of the Gencfa Lus, A.I.(1991): Caracterizaci6ngeoqufmicade los

leucogranitosde Lumbrales:influencia de la deformaci6n

Basque Country Govemmenl. We thank Dr. Brad

en el modelomagmdtico.Definici6n de dos tendenciase

Jolliff for his suggestions,which have improved the

implicaci6n en los procesospetrogendticos.EsaGeol, 4fl,

manuscript. We also express our gratitude to Drs.

t3-31.

Robert F. Martin and J.T. O'Connorfor their helpful

criticism.

GoNzAroConneq J.C. (1981):Estudio geol6gicodel campo

filoniano de la Fregeneda(Salamanca).Tesis Licenc.,

Univ. SalamancaSalamancaSpain.

Rmmsvcrs

Atnws, L.H., PtrrsoN,

W.H. & Kranns,M.M. (1952): Ilruncwr,nr, R.H., Garmar, K., GAu.AcIrR" V. & Bercn,

Association

of rubidiumandpotassium

andtheir abunJ.H. (1994): Tourmaline in the central Swedishore disdance in igneous rocks and meteorites.Geochim,

trict- Mbrcral. Deposita29, 189-205.

Cosmochim.Acta 2, 229-242.

Appr,s\4AN,

D.E. & EvANs,H.T., Jn. (1973):Iob 9214;

indexingandleast-squares

refinement

of powderdiftaction data U.S.Geol.Suw.,Comput.Contrib.20QVZ/S

Doc PB2.16IE$.

BBA,F. (1976):Anomalfageoqufinicade los granitoides

- Salamanca

calcoalcalinos

hercfnicos

del&eaCdceres

Tmplicaciones

petrogen6ticas.

Zamora(Espafra).

^Srudla

Geologica Salmantic

ensia ll, 25:73.

SANafi4 J.G. & Smneno hflo, M. (1988): Una

compilaci6ngeoqufmicapara los granitoidesdel macizo

Hesp6rico. ,lz Geologia de los Granitoides y Rocas

Asociadasdel Macizo Hesp€rico.Edit. Rueda Madrid,

Spain(87-192).

& Uctpos, J.M. (1976): Anatexia inducida:

petrog6nesisde los granitos hesp6ricos de tendencia

alcalina. I. Leucogranitos del 6rea O de Zamora y

Salamanca.Sndia GeologicaSalmanticen*iall, 9-24..

Ilqvnv, D.J. & Gutooru, C.V. (1985): Tourmaline as a

petrogenetic indicator mineral: an example from the

staurolite-grademetapelitesof NW Maine. Am- Mineral.

70, l-15.

Jorm, 8.L., Pem<e, J.J. & Leu" J.C. (1987): Mineral

recordersof pegnatite intemal evolution:REE contentsof

tourmaline from the Bob Ingersoll pegmatite, South

Dakota-GeochfunCosmochint.Acta 51. 22?5-2232.

& Smenm., C.K. (1986):Tourmalineas

a recorder of pegmatite evolution: Bob Ingersoll

pegmatite,Black Hills, South Dakota.fun Mtuural. 11,

n2-5@.

Kessou-Founr.anan, A. (1990): Chemical variations in

tourmalines from pegmatite ocqurencqs in Chalkidiki

Peninsul4 northern Grwe. Sclweiz Mineral. Petrogr.

Mtn.70,55-65.

-

Cemucmo, M.A. (1981): Granitoidesdel CentroOestede la

hovincia de Salamanca-Clasificaci6n y correlaci6n.

Cuad,Inborat, XeoI. de Iaxe 2.4549.

& Mcsanpn, IC (1994):Chemicalcompositionof

tourmaline in quartz veins from Nea Roda and Thasos

areasin Macedonia-northern Grewq Can Mincral. 32.

6U7-615.

848

TIIE CANADIAN

Knvc, R.W., KERRTCH,

R.W. & Deooan, R. (1988): REE

distributionsin tourmaline:an INAA techniqueinvolving

pretreatment by B volatilization, Am" Mineral. 73,

424431.

MINERALOGIST

Pnarxo, F. & Smrms, R.H. (1992):The FeO(FeO + MgO)

ratio of tourmaline:a useft.rlindicator of spatialvariations

in granite-related hydrothermal mineral deposits.

Geochsn.Explor. 42, 37l-381.

I-6pw.Htze, M., Canmcrno,A. & Goxzerc, J.C. (1982): RoDA, E. & PEseuERA,A. (1995): Micas of the

Estudio geol6gico del campofiloniano de La Fregeneda

muscovite-lepidolite series from the Fregenedapeg(Salamanca).Sndia GeolngicaSalmanticensia17, 89-98.

matites(Salamanc1Spain).Mincral. Petrol. (in press).

& Canmcrno, M.A. (1988): El pluronismo

Herclnico de la penillanurasalmantino-zamorana

(centrooestede Espa<0241>a):visi6n de conjuntoetr el contexto

geol6gico regional. ^Iz Geologla de los Granitoides y

Rocas Asociadas del Macizo Hespdrico. EdiL Rueda

Madrid,Spain(53-68).

& ManrfNsz CATALAN,J.R. (1988): Slntesis

estructural de los granitoides Hercfnicos del macizo

Hesp6rico. In Geologfa de los Granitoides y Rocas

Asociadasdel Macizo Hespdrico.Erdit. Ruedq Madri{

Spain(195-210).

& VH.Asco,F. (1991):The pegmatitesof

the Fregeneda area, Salamanca, Spain. /z Source,

Transport and Deposition of Metals (M. Pagel &

J.L. l,eroy, eds.).Balkema RotterdanqThe Netherlands

(80r-806).

& -(1993):

Mica andK-feldspar

asindicatorsof pegmatiteevolutionin the Fregenedaarea,

Salamanca, Spain. /n Cunent Research in Geology

Applied to Ore Deposits @. Fenoll Hach-Alf, J. TorresRuiz & F. Gervilla, eds.).l,a Guioconda Granada,Spain

(653-6s6).

Marwnc, D.A.C. (1982): Chemical and morphological Snnanm, C.K., Papncq J.J., Snaox, S.B., Law, J.C. &

variationin tourmalinesfrom theHub Kapongbatholithof

CmIsrIAN, R.P. (1984): Peematit€/walhockinteractions,

peninsularThailand,Mineral. Mag. 45, 139-147.

Black Hills, South Dakota: progressiveboron metasomatism adjacent to the Tip Top peguatite. Geochim,

Menrh{ez FrrurAr.Dsz, F.J. (1974): Estadio del drea

Cosrutchim.Acta 4E,2563-2579.

mznmlfica y gran{tica de los Anibes del Dwro (Prov.

de Salamancay hmora). Ph.D. thesis,Univ. Salamanc4 TAUsoN,L.V. (1965): Factorsin the distribution ofthe trace

Salamanc4Spain.

elements during the crystallization of mapas. Phys.

Chen.Eanh6,2L5-249.

Mrctrarrors, K. & Kessolr-FonRNARAKr,A. (1994):

Tourmaline concentrations in migmatitic metasedimentary rocks of the Riziana and Kolchiko areasin

Macedonia,northernGreece.Eur. J. Mineral.6,557-569.

Newe, A.M.R. (1974): Geochemistryof tourmaline (schorIite) from grulites, aplites and pegmatitesfrom northem

Portugal.Geochim,Cosmochim.Acta 38, L307-13L7.

Received July 5, 1994, revised manuscript accepted

Janunry 11, 1995.