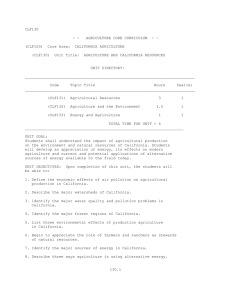

AGRICULTURAL POLICY ACTION PLAN (APAP)

advertisement