Teaching Restorative Practices with Classroom Circles

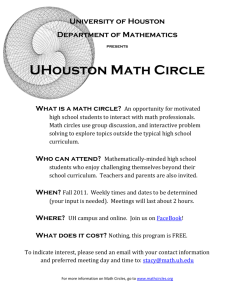

advertisement