[PDF - City of Chicago

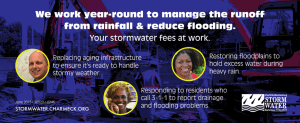

advertisement