An Objective and Practical Test for Adjudicating Political Patronage

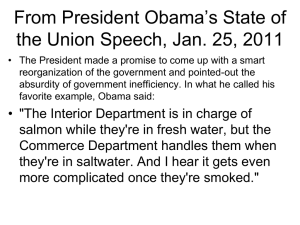

advertisement