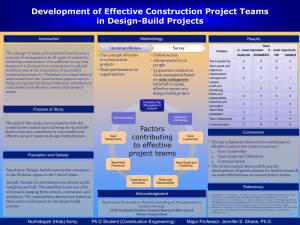

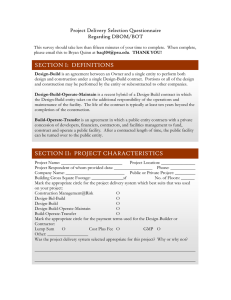

Design-Build Legal Issues

advertisement