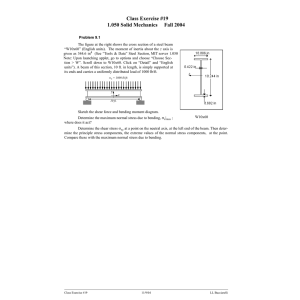

connections between steel and other materials

advertisement