Predictive signs of difficult intubation

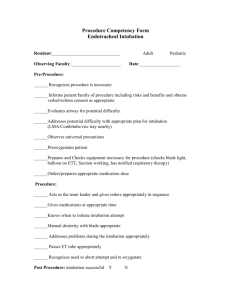

advertisement

Predictive signs of difficult intubation Pierre Diemunsch, Thierry Pottecher Studies carried out in the United Kingdom in the 1980s established that each year, 3 pregnant women die due to impossible airway control. On a global scale, difficult or impossible intubation kills an estimated 600 people a year1. Difficulties related to certain extreme situations, such as battlefields and lack of specific training, are indisputable factors in impossible airway control2. The acute awareness of practitioners (workshops in all major congresses), the development of fibroscopy, the introduction of algorithms and a generalization in the use of the laryngeal mask have contributed to a decrease in complications of sudden impossible ventilation as observed in the US over the past decade3. Screening for high-risk situations using simple clinical signs can avoid complications but is not sufficient on its own, because the identification of a problem does not guarantee its resolution. Nonetheless, it is crucial to recognize patients for whom mask ventilation or intubation is potentially difficult, in order to take preventative measures and to be prepared to apply first-line treatment, which will be optimized by avoiding the stress of a surprise situation. Difficult intubation has often been associated with difficult laryngoscopy. Laryngoscopy provides a more or less complete view of the glottis, making intubation relatively easy. Cormack and Lehane4 have defined 4 grades of laryngoscopic view, according to the structures that can be visualized (table 1). Intubation is easy for grade I and slightly more difficult for grade II, but this is generally improved by external manipulation of the larynx. Grade III corresponds to severe intubation difficulties, and grade IV usually corresponds to an impossible intubation. This relationship is not categorical. It is excessive to completely associate the conditions of difficult laryngoscopy and difficult intubation. A study carried out by Wilson (table 3) reveals considerable variations in the reported incidence of difficult laryngoscopies, defined as corresponding to a Cormack grade greater than II. These differences are attributed to variations between operators and to whether external laryngeal pressure is applied or not. Moreover, these figures have very little to do with those reported for difficult intubations. Grade Structures identified by direct laryngoscopy Visualization of the entire laryngeal aperture I Visualization limited to the posterior portion of the laryngeal aperture, incomplete II visualization of the cords Visualization limited to the epiglottis, no visualization of the laryngeal aperture III Visualization limited to the soft palate, no visualization of the epiglottis IV TABLE 1 The 4 grades of Cormack and Lehane. These grades, defined for obstetric patients, are associated with increasing orotracheal intubation difficulties. Their correlation with the 4 Mallampati classes as modified by Samsoon and Young is neither very sensitive nor very specific. 169 Predictive signs of difficult intubation Based on a study of 500 patients, Cook5 proposed a 3-grade classification of laryngoscopic views. This classification is better correlated to intubation difficulties than the classical grades of Cormack and Lehane. Quality of the laryngoscopy Easy Restricted Difficult Criteria of Cook Laryngeal inlet visible Visibility of posterior glottic structures (posterior commissure or arytenoids) OR of epiglottis that can be lifted No laryngeal structures visible OR epiglottis visible but cannot be lifted Grade of Cormack and Lehane I II and III III and IV Impossible intubation Before declaring that a maneuver is difficult or impossible, it is essential to take into account the circumstances involved in performing it by using a definition of optimal attempt. Definition and quantification of the difficulty are 2 other elements that should be standardized to interpret and compare clinical study data. Criteria of definition of optimal attempt Orotracheal intubation Mask ventilation 1- two-person additive/synergistic effort for 1- reasonably experienced laryngoscopist optimal jaw thrust and mask seal 2- no significant muscle tone 2- large oropharyngeal airway 3- optimal sniff position 4- optimal external laryngeal pressure 5- change length of blade once 3- large bilateral nasopharyngeal airways 6- change type of blade once TABLE 2 Criteria of definition of optimal attempt at intubation and mask ventilation. When these criteria are fulfilled, failure involves the diagnosis of impossibility and requires an alternative solution. The advantage of the sniff position was recently contested6. As compared to a simple extension of the head, this position only improves laryngoscopy in obese patients or when the mobility of the neck is limited. 170 Predictive signs of difficult intubation Incidence of various degrees of difficult intubation (16 clinical studies) Final result: Means required Cormack Incidenc intubation and Lehane e (%) Possible Multiple attempts and/or blades II or III 1 to 18 Possible Multiple attempts and/or blades and/or laryngoscopists III 1 to 4 Impossible III or IV 0.05 to 0.35 iiiv*, afterTranstracheal approach, jet ventilation, life-saving 0.0001 to effects or measures 0.02 death Incidence of difficult intubation (Savva, 1994) Intubation on bougie after 2 unsuccessful attempts >II 4.9 Incidence of difficult laryngoscopies (Wilson, 1988) Without laryngeal compression; n=431 >II 9.3 With laryngeal compression; n=202 >II 5.9 With laryngeal compression; n=778; prospective study >II 1.6 TABLE 3 Incidences of various degrees of difficult intubation and difficult laryngoscopies. *iiiv = impossible intubation and impossible ventilation (from Reisner, 1999; Savva, 1994; Wilson, 1988). In 1997, Adnet7 proposed a quantitative score for difficult intubation, aiming to standardize evaluations and to permit comparisons between various predictive tests and management techniques for difficult intubation. Parameters Number of attempts over 1 Number of operators over 1 Number of alternative techniques Cormack and Lehane grade – 1 (grade 1 = 0) Normal traction strength (0) or abnormal (1) Laryngeal pressure: no (0) or yes (1) except for Sellick Vocal cords in abduction (0) or adduction (1) Degree of difficulty (sum of parameters) Total = intubation difficulty score 0 = easy, ideal 0 <total <=5 = slight difficulty 5 <total = moderate to major difficulty ∞ corresponds to impossible intubation Distribution of difficulty scores hospitalized patients; n=289 (Adnet et al., 1997) score =0 53% (time: 6 to 50s; mean:18s) score >5 6.3% Distribution of difficulty scores pre-hospitalized patients; n=311 (Adnet et al., 1997) score =0 28.2% score >5 16.1 % with 1 impossible (>17) 171 Predictive signs of difficult intubation Predictive signs of intubation difficulty We lack predictive criteria that are simple, rapid, affordable, reliable, sensitive and specific, and that have good positive and negative predictive values. 1 – Anatomical criteria Checking for elements that indicate potential intubation difficulties is an essential part of the anesthesia workup. In emergencies, this assessment can be limited to checking for prostheses and to the Mallampati classification and Wilson score (tables 4 and 5). Most assessments proposed include common points or variable assessments of the same criteria (neck extension and sternomental distance, for example). 1. Mallampati classification8 This is established when the patient is awake, either sitting or standing. The patient is asked to open the mouth as wide as possible, and to stick out the tongue as far as possible, without phonation (table 4). The classification was initially limited to the first 3 classes, and was completed by the addition of class IV represented by a limited view of the hard palate. The correlation with the Cormack and Lehane grades is not very reliable for Mallampati classes II and III, because patients with these intermediary airway classifications have a relatively uniform distribution of the 4 grades of laryngoscopic view. However, there is a good correlation between the observance of a class I and a grade I laryngoscopy. Likewise, a class IV is generally associated with a grade III or IV. The mediocre performance of the Mallampati classification has been attributed to errors in methodology, such as examining the patient in supine position, having the patient say “ah” (phonation that falsely improves the view), or allowing the patient to arch his or her tongue (falsely obscuring the view). Variations between observers are an additional source of false positives and false negatives for the Mallampati classification, which is not sufficient on its own to predict difficult laryngoscopy nor, a fortiori, difficult intubation. The insufficiency of the Mallampati classification has been specifically shown for obese patients9. These data indicate that this classification should no longer be considered individually capable of predicting, with precision, what the laryngoscopic view will be10. Combining the assessment of the mouth opening improves the specificity without altering the sensitivity of the Mallampati classification as a predictor of difficult intubation11. Class I II III IV Visible structures (patient upright, maximal opening of mouth and protrusion of tongue) Uvula, fauces, soft palate, hard palate Fauces, soft palate, hard palate Soft palate, hard palate Hard palate alone TABLE 4 Mallampati classification modified by Samsoon and Young (addition of class IV) and outcome of test. 172 Predictive signs of difficult intubation Figure: Mallampati classification Mallampati class predictive of a DI >II True positives (%) 55 False positives (%) 5 Ezri has suggested adding a class 0 to the 4 others. Class 0 is defined as the visualization of the epiglottis with an open mouth and protruding tongue12. The incidence of class 0 is 1.18% in the author’s study. It is consistently associated with a Cormack and Lehane grade I laryngoscopic view. 2. Wilson score Wilson’s study (1988)13 was an important development in the attempt to deductively identify patients for whom intubation will be difficult. It should be emphasized that this study tests the predictability of difficult laryngoscopy and not difficult intubation. Criterion Weight (kg) Head and neck mobility (degrees) Mandibular mobility Retrognathism Prominence of upper incisors 0 <90 >90 Points 1 90-110 90 2 >110 <90 MO* >5 cm or subluxation† >0 None None MO* <5 cm and subluxation† =0 Moderate Moderate MO* <5 cm and subluxation† <0 Severe Severe TABLE 5 Wilson score. *MO: mouth opening; †subluxation: possibility of advancing the mandibular incisors in front of the maxillary incisors (>0); or just to their level (=0); or impossibility of advancing the mandible in relation to the maxilla (<0). A score of 2 or more is predictive of a difficult (intubation) laryngoscopy. 173 Predictive signs of difficult intubation Performances of the score depending on the chosen threshold (prospective study). Choice of threshold value of Wilson score >=4 >=3 >=2 >=1 True positives (%) 42 50 75 92 False positives (%) 0.8 4.6 12.1 26.6 No factor is all-important. Several simple indicators are assessed by the mobility of the head and neck (cervical flexion and atlantooccipital joint extension) as well as by mandibular mobility (distance between upper and lower incisors and temporomandibular joint mobility). Other classical items, such as a short, thick neck, are sufficiently represented by the weight of the patient, which is easier to assess quantitatively. The elements describing the relative place of the tongue in the mouth and how it interferes with the view of the laryngeal aperture, are found together in the subjective assessment of the prominence of the upper incisors and of the retrognathism. It is easy and advisable to complete these criteria with the Mallampati classification. When a threshold value of 2 (Wilson score) is chosen to predict a difficult laryngoscopy, 75% of difficult cases were correctly detected (true positives) and 12.1% of easy cases were incorrectly detected as being difficult (false positives). The author calculates that for an annual activity of 10 000 patients, of whom 1.5% (150) have a difficult laryngoscopy, 9 true positives are detected per month for every 3 patients who are overlooked during screening (total =12). Out of the 9850 easy patients, 12.1% unduly prompt the implementation of specific measures that are useless and sometimes extensive. The false positives (1192=9850*12.1%) are the cause of 99 false alerts per month. These data illustrate the relatively weak power of the tests and the absolute need to train all anesthesiologists in difficult intubation techniques. This skill, combined with a sufficient availability of fibroscopes, enables practitioners to deal with sudden difficulties and makes anticipatory measures commonplace. This outweighs the logistical disadvantages of taking numerous false positives into consideration. 3. El-Ganzouri score14 Established according to the same principle as the Wilson score, it includes similar criteria, in addition to the thyromental distance, Mallampati classification and history of DI. A value of 4 or more has a better predictive value than the Mallampati classification. It is a predictive score for difficult laryngoscopies, established from a study of 10 507 patients of whom 5.1% are grade III and 1% are grade IV according to Cormack and Lehane. Criterion Weight (kg) Head and neck mobility (degrees) Mouth opening Subluxation >0 Thyromental distance Mallampati class History of DI 174 0 <90 >90 Points 1 90-110 90±10 2 >110 <80 >=4 cm possible >6.5 cm I no <4 cm not possible 6-6.5 cm II possible <6 cm III established Predictive signs of difficult intubation 4. The three criteria of Bellhouse In 1988, Bellhouse15 published the results of a comparison between radiographic studies of 19 patients for whom intubation had been difficult and those of 14 patients for whom intubation had been easy. He used these results to identify the following criteria that together predict intubation difficulty: - restriction of atlantooccipital joint extension (less than 35 degrees); - reduced mandibular space; - enlarged tongue (versus pharyngeal) size. The atlantooccipital joint extension is measured by moving the plane of the occlusal surface of the upper teeth. When the patient sits facing forward with his or her head erect, this plane is horizontal. When a normal patient extends the atlantooccipital joint as much as possible, he or she can produce a 35° angle between the horizontal and extended planes. The mandibular space is assessed by the thyromental distance, which should be at least 5 cm (or 3 fingerbreadths) long. This distance evaluates the horizontal length of the mandible (>9 cm). A short thyromental distance can be combined with a retrognathism and a relative macroglossia. It generally coincides with a high Mallampati classification because the tongue that is more globular obscures the view of the pharynx. When the mandibular space is large, the tongue can be easily compressed into this space and the larynx, which lies relatively posterior, can be more easily visualized with direct laryngoscopy. Forward protrusion of the mandible contributes positively to a large mandibular space. 5. Sternomental distance The comparison of 4 predictive tests on the same population (n=350)16 confirms that a Mallampati classification >II is not reliable on its own. Measurement of sternomental distance proved to be more sensitive and more specific, with a threshold value of 12.5 (head fully extended on the neck and the mouth closed). The thyromental distance (less or equal to 6.5 cm) was less useful, as was the inability to bring the mandibular teeth anterior to the maxillary teeth (subluxation), refuting the results reported by Wilson. Test (n=350) (Savva, 1994) Mallampati >II Thyromental distance <=6.5 cm Sternomental distance <=12.5 cm Subluxation 0 or <0 Sensitivity (%) Specificity (%) 64.7 64.7 82.4 29.4 66.1 81.4 88.6 85.0 Positive predictive value (%) 8.9 15.1 26.9 9.1 6. Synthesis Benumof (1999-2001) grouped together 11 main elements of a physical examination and the criteria that must be met in order to indicate that intubation will not be difficult (table 6). This evaluation uses the most relevant elements of the main tests or scores proposed. It is carried out easily and quickly, and requires no specific equipment. Complementary elements are obtained by questioning the patient and studying previous anesthesia reports, keeping in mind that intubation difficulty can vary in the same patient from one procedure to another, and even only a few hours apart17. Obesity and mammary hypertrophy usually play important roles. A criteria that is pathologic to the point of establishing the diagnosis of an impossible intubation on its own is exceptionally rare. Usually, the probability of a DI is backed up by several, converging elements. The reliability of the assessment increases with the number of criteria that are considered. Wong confirms this conclusion in his series of 411 women. The study indicates that pregnancy does not increase the risk of DI (prevalence of 1.99% versus 1.55% for non-pregnant women)18. 175 Predictive signs of difficult intubation 11 elements of the examination Length of the upper incisors Involuntary anterior overriding of the maxillary teeth on the mandibular teeth (retrognathism) Voluntary protrusion of the mandibular teeth anterior to the maxillary teeth Criteria in favor of an easy intubation Short incisors – qualitative evaluation No overriding of the maxillary teeth on the mandibular teeth Inter-incisor distance (mouth opening) Mallampati classification (sitting position) Configuration of the palate Thyromental distance (mandibular space) Mandibular space compliance Length of neck Thickness of neck Range of motion of head and neck Anterior protrusion of the mandibular teeth relative to the maxillary teeth (subluxation of the TMJ) Over 3 cm I or II Should not appear very narrow or highly arched 5 cm or 3 fingerbreadths Qualitative palpation of normal resilience/softness Not a short neck – qualitative evaluation Not a thick neck – qualitative evaluation Neck flexed 35° on chest, and head extended 80° on the neck (ie sniffing position) TABLE 6 Main elements of the examination to detect difficult intubation. The 11 items are presented in logical order, superiorly to inferiorly (teeth followed by mouth and then neck); no element is sufficient on its own. (TMJ: temporomandibular joint). From Benumof, 1999. For Karkouti19, the ideal combination includes 3 airway tests: mouth opening, chin protrusion and atlantooccipital extension. This preference is based on a multivariable analysis of predictive criteria, in an observational study of 461 patients of whom 38 had a DI. The conclusions reached by Bernumof are based on common sense and on the author’s expertise. 7. Paraclinical examinations for systematic detection of DI Among the paraclinical evaluations, indirect laryngoscopy seems to be the easiest to perform (sitting position, tongue held out by operator, angled mirror) and the easiest to interpret. A view that is equivalent to Cormack and Lehane grades III and IV is predictive of a direct laryngoscopy revealing the same grades and of difficult intubation. The positive predictive value, sensitivity and specificity of this test are better than those of the Mallampati classification and of the Wilson score20. This examination may not be possible to perform in certain patients, including 15% who have a strong gag reflex, and others who cannot sit up or who refuse it. Test (n=6148, DI: 1.3%) (Yamamoto, 1997) Wilson score >2 Mallampati classification >2 Indirect laryngoscopy; grade >II Sensitivity (%) Specificity (%) 55.4 67.9 69.2 86.1 52.5 98.4 Positive predictive value (%) 5.9 2.2 31.0 The combination of clinical and radiological criteria proposed by Naguib is interesting from a retrospective point of view, but cannot be systematically applied as a detection tool21. 176 Predictive signs of difficult intubation 2 – High-risk groups Intubation is generally considered more difficult in pregnant women and in otolaryngology (ENT)22 and traumatology patients. Contradictory data have been reported, however, notably in obstetrics17. Moreover, certain pathologies are particularly predisposing. Among the most common of these is diabetes. To check if a diabetic patient is at risk, ask him or her to bring the hands together as if praying. If the fifth fingers of the hands cannot be flat against one another, there is probably ligament thickening of the finger joints (and in the TMJ and the cervical spine), and difficult intubation should be anticipated. Another test that has recently been proposed is a palm print study of the patient’s dominant hand. A grade above 0 is considered a more sensitive predictor of difficult laryngoscopy than the Mallampati classification, the thyromental distance and the degree of neck extension23; (in this study, the praying test was not compared to the palm print test). Palm print Grade 0 – View of all phalangeal surfaces Grade 1 – Phalangeal surfaces of fourth or fifth fingers missing from print Grade 2 – Phalangeal surfaces of the second to fifth fingers missing from print Grade 3 – Print of fingertips only. Acromegaly is also considered a risk factor. Difficult intubation occurs in about 10% of patients with this disease24. Obesity by itself, including morbid obesity (BMI>35 Kg/m2) was not always considered a factor in difficult laryngoscopy25. The combination of obesity and lack of teeth, however, is strongly predisposing. A more recent series conversely suggested that difficult tracheal intubation is more common in obese than in lean patients, with a difficult intubation rate of 15.5% in obese patients (BMI>35 Kg/m2) compared to 2.2% in lean patients (BMI<30 Kg/m2) respectively. Desaturation is common and fast occurring with difficult intubation in obese patients26. In general, problems linked to congenital disease, rheumatic conditions, local pathologies and previous history of trauma are easily identified during the physical exam or by questioning the patient. In otolaryngology, surgeons who are prepared to perform a direct tracheal approach in case of impossible intubation are immediately available to assist the anesthesiologist. Lingual papillomatosis and angioedemas can also be formidable pitfalls. Examples of obvious or less obvious situations that predispose to difficult intubation: - congenital facial and upper airway deformities; - maxillofacial and airway trauma (current or previous); - airway tumors and abscesses; - immobile cervical spine; - fibrosis of the face and neck from burns or radiation exposure; - obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS)27; - history of neurosurgical procedures, with or without division of the temporal muscle, that can lead to pseudoankylosis of the mandible28. - tongue piercing29. 177 Predictive signs of difficult intubation 3 – Clinical index Clinical multifactorial indexes have been described to predict difficult intubation. Defining difficult intubation as the failed attempt of 2 anesthesiologists to use basic direct laryngoscopy, Arné30 has developed a clinical index that obtains predictive scores with a sensitivity and specificity of 94% and 96% in general surgery, 90% and 93% in ENT non-cancer surgery, and 92% and 66% in ENT cancer surgery. The defined index was validated in a prospective study (n=1090) after being established in an initial study (n=1200). The overall incidence of difficult intubation for all patients is 4.2%. No impossible intubation was reported. The factors taken into consideration are: 1. Weight, age and height 2. History of DI (if patient was informed) 3. Predisposing pathologies such as facial deformities, acromegaly, rheumatic conditions o the neck, ENT tumors, diabetes 4. Symptoms of respiratory tract diseases such as dyspnea, dysphonia, dysphagia and sleep apnea in particular 5. Mandibular mobility as in the Wilson score, but with a 3.5 cm mouth opening 6. Mobility of the head and the neck as in the Wilson score 7. Prominence of the upper incisors as in the Wilson score 8. Aspect of the neck: short and thick or not 9. Thyromental distance, > or <6.5 cm 10. Mallampati classification The statistical analysis based on 1200 observations was used to assign point values to each of these factors in proportion to regression coefficients representing the relative weight of each predictive intubation difficulty factor, which was validated in the second prospective study of 1090 patients. Criteria Simplified value Past history of DI 10 Predisposing pathologies 5 Respiratory symptoms 3 MO >5 cm or subluxation >0 0 3.5 cm<MO<5 cm and subluxation =0 3 MO <3.5 cm and subluxation <0 13 Thyromental distance < 6.5 cm 4 Mobility of head and neck >100° 0 Mobility of head and neck 80-100° 2 Mobility of head and neck <80° 5 Mallampati classification 1 0 Mallampati classification 2 2 Mallampati classification 3 6 Mallampati classification 4 8 Maximum total 48 With 11 as the threshold value for this index, the test gave the following results: Sensitivity: 93% Specificity: 93% PPV: 34% NPV: 99% General population Validation study: n=1090 Difficult intubation: 3.8% Opinions concerning the usefulness of this type of index are sometimes very negative31. Nevertheless, they seem to play a justifiable role in the evaluation of situations that are neither obviously easy nor obviously difficult. 178 Predictive signs of difficult intubation Conclusions Predictive tests of difficult intubation are numerous. None are perfect. The reproducibility of the tests from one observer to another is inconsistent. A certain confusion exists between difficult laryngoscopy and difficult intubation. A certain amount of false negatives will persist, no matter what method of detection is used. Prevention is the best cure. However, foreseeing, when possible, does not guarantee prevention32. There is a perceptible association in the literature between foreseeing difficulty and preventing death due to impossible intubation. Since our final goal is the latter, we should direct our efforts towards the management of DI as much as towards detecting it. References 1. King TA, Adams AP. Failed tracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth 1990; 65:400-14. 2. Abraham RB, Yaalom R, Kluger Y, Stein M, Weinbroum A, Paret G. Problematic intubation in soldiers: are there predisposing factors? Mil Med 2000;165:111-3. 3. Benumof JL. The ASA difficult airway algorithm: New thoughts/considerations. ASA Refresher Course Lectures 1999; 134. 4. Cormack RS, Lehane J. Difficult tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Anaesthesia 1984; 39:1105-11. 5. Cook TM. A new practical classification of laryngeal view. Anaesthesia 2000;55:274-9. 6. Adnet F, Baillard C, Borron S, Denantes C, Lefebvre L, Galinski M, Martinez C, Cupa M, Lapostolle F. Randomized study comparing the "sniffing position" with simple head extension for laryngoscopic view in elective surgery patients. Anesthesiology 2001;95:836-41. 7. Adnet F, Borron SW, Racine SX, Clemessy JL, Fournier JL, Plaisance P, Lapandry C. The intubation difficulty scale (IDS). Proposal and evaluation of new score characterizing the difficulty of endotracheal intubation. Anesthesiology 1997; 87:1290-7. 8. Mallampati SR, Gatt SP, Gugino LD et al. A clinical sign to predict difficult tracheal intubation. A prospective study. Can J Anaesth 1985;32:429-34. 9. Lavaut E, Juvin P, Dupont H, Demetriou M, Desmonts JM. Difficult intubation is not predicted by Mallampati's criteria in morbidly obese patients. Anesthesiology 2000;A-1364. 10.Calder I. Acromegaly, the Mallampati, and difficult intubation. Anesthesiology 2001;94:11491150. 11. Pottecher T, Velten M, Galani M, Forrler M. Valeur comparee des signes cliniques d'intubation difficile chez la femme. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 1991; 10:430-5. 12. Ezri T, Warters RD, Szmuk P, Saad-Eddin H, Geva D, Katz J, Hagberg C. The incidence of class "zero" airway and the impact of Mallampati score, age, sex, and body mass index on prediction of laryngoscopy grade. Anesth Analg 2001;93:1073-5. 13. Wilson ME, Spiegelhalter D, Robertson JA, Lesser P. Predicting difficult intubation. Br J Anaesth 1988, 61:211-6. 14. El-Ganzouri AR, McCarthy RJ, Tuman KJ, Tanck EN, Ivankovich AD. Preoperative airway assessment: predictive value of a multivariate risk index. Anesth Analg 1996; 82:1197–204. 15. Bellhouse CP, Dore C. Criteria for estimating likelihood of difficulty of endotracheal intubation with the Macintosh laryngoscope. Anaesth Intensive Care 1988;16:329-37. 16. Savva D. Prediction of difficult tracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth 1994; 73:149-53. 17. Farcon E, Kim M, Marx G. Changing Mallampati score during labour. Can J Anaesth. 1994; 41:50-1. 18. Wong SH, Hung CT. Prevalence and prediction of difficult intubation in Chinese women. Anaesth Intensive Care 1999;27:49-52. 19. Karkouti K, Rose DK, Wigglesworth D, Cohen MM. Predicting difficult intubation: a multivariable analysis. Can J Anaesth 2000;47:730-9. 20. Yamamoto K, Tsubokawa T, Shibata K, Ohmura S, Nitta S, Kobayashi T. Predicting difficult intubation with indirect laryngoscopy. Anesthesiology 1997; 86:316-21. 21. Naguib M, Malabarey T, AlSatli RA, Al Damegh S, Samarkandi AH. Predictive models for difficult laryngoscopy and intubation. A clinical, radiologic and three-dimensional computer imaging study. Can J Anaesth 1999;46:748-59. 179 Predictive signs of difficult intubation 22. Arne J. Criteria predictive of difficult intubation in ORL surgery. Rev Med Suisse Romande 1999;119:861-3. 23. Vani V, Kamath SK, Naik LD. The palm print as a sensitive predictor of difficult laryngoscopy in diabetics: a comparison with other airway evaluation indices. J Postgrad Med 2000; 46: 75-79 24. Schmitt H, Buchfelder M, Radespiel-Tröger M, Fahlbusch R. Difficult intubation in acromegalic patients: incidence and predictability Anesthesiology 2000;93:110-4. 25. Szmuk P, Ezri T, Weisenberg M, Medalion B, Warters RD. Increased body mass index is not a predictor of difficult laryngoscopy. Anesthesiology 2001; 95:A1137 26. Juvin P, Lavaut E, Dupont H, Lefevre P, Demetriou M, Dumoulin JL, Desmonts JM. Difficult tracheal intubation is more common in obese than in lean patients. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:595600. 27. Hiremath AS, Hillman DR, James AL, Noffsinger WJ, Platt PR, Singer SL. Relationship between difficult tracheal intubation and obstructive sleep apnoea. Br. J. Anaesth. 1998; 80:606-11. 28. Kabbaj S, Ismaili H, Maazouzi W. Intubation impossible après intervention neurochirurgicale. Ann Fr Anesth Réanim 2001;20:735-6. 29. Kuczkowski KM, Benumof JL.Tongue piercing and obstetric anesthesia: is there cause for concern? J Clin Anesth. 2002;14:447-8. 30. Arné J, Descoins P, Fusciardi J, Ingrand P, Ferrier B, Boudigues D, Ariès J. Preoperative assessment for difficult intubation in general and ENT surgery: predictive value of a clinical multivariate risk index. Br. J. Anaesth. 1998; 80:140-6. 31. Lang SA. Practical airway assessment. Br. J. Anaesth. 1998; 81:655. 32. Yentis S. M. Predicting difficult intubation - worthwhile exercise or pointless ritual?. Anaesthesia. 2002 ;57:105-109. 180