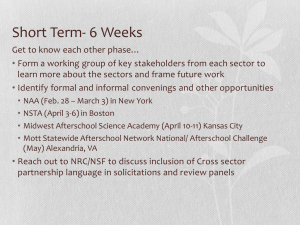

Expanding and Opportunities

advertisement