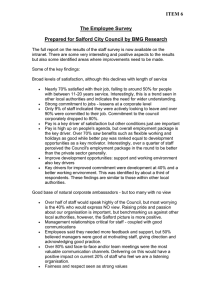

capacity and competency requirements in local government

advertisement