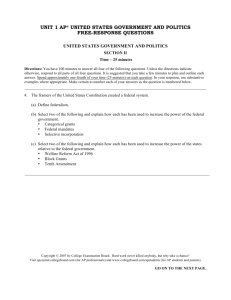

AP Physics Course Description

advertisement