Instructional Strategies: Advance & Graphic Organizers

advertisement

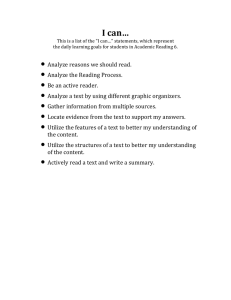

Instructional Strategy Lessons for Educators Secondary Education (ISLES-S) ORGANIZERS: Advance Organizers Graphic Organizers Declarative Knowledge Level Advance Organizers Instructional Strategies • First Impressions • How can I prepare students to learn new concepts? • How can I help students connect new information with previously learned information? • What tools are available to aid students in collecting information about concepts for future reference? Section 1 Objectives: Definition and Purpose Students will be able to... 1. Define advance organizers. Advance organizers can have a profound effect on students’ success during a lesson, especially 2. Identify which component of the lesson should include advance organizers. value of advance organizers, it helps to experience learning without them. Check out the video 3. Describe examples of the use of advance organizers. 4. Recognize the benefits of using advance organizers. when that lesson requires them to receive, store, and recall new information. To grasp the Minute Earth: Do Fetuses Poop?, an animation-enhanced lecture explaining how fetuses obtain and dispose of nutrients. Guiding Questions The Burden of Learning Without Advance Organizers How might the addition of an advance organizer help a student learn the information presented in this lesson? Notice that, without the advantage of any setup, without any forecasting of content or accessing of prior knowledge, discerning what is important and learning it to the point of recall is rather challenging. What’s This? Advance organizers... • are statements, activities, or graphic organizers that help the learner anticipate and organize new information. • are used at the beginning of lessons in which new information is to be learned. • often call on prior knowledge, so as to connect new learning to an existing cognitive structure. • indicate to the learner what information from a lesson will be important. Instructional Strategies 3 Take a Look During which component(s) of the lesson do you use advance organizers? By definition, advance organizers are appropriate at the beginning of the lesson--in advance of new learning--and can be used during the focus, review, and statement of the objectives portions of the lesson. An advance organizer is similar to a meeting agenda in which the content is outlined. Teachers can also refer back to points established in the advance organizer throughout the lesson. With a narrative advance organizer, for example, the teacher might refer back to parts of a story told to introduce the day’s lesson. With an anticipation guide, students can check the accuracy of their anticipated responses while they listen to a lecture or view a video. How do you use advance organizers? Consider the amount of time needed for the entire lesson and the context within which the advance organizer will be placed. For instance, if the entire lesson will need to occur within a 45 minute period, do not use 30 minutes for an advance organizer activity. There are a variety of advanced organizers, including: Expository, a description of a new concept to be presented, highlighting important content. Narrative, an anecdote that connects personal experiences or real world events to the new concept to be presented. Skimming, a preview of readings that will occur later in the lesson, paying special attention to headings, bold print, etc. Graphic, such as KWLs, flow charts, and other visual tools that tap into prior knowledge or imply the scope and organization of new content. 4 Students should fully understand the purpose of any advance organizer that you assign. The statement of objectives, an obvious but necessary part of the lesson, will help students focus that prior knowledge they tapped into--what is at this point a disorganized list scattered across their teenage brains. Instructional Strategies 5 Section 2 Real Life Examples How will advance organizers look in my classroom? Classroom Example of an Advance Organizer In a high school Civics and Economics course, a class is preparing to learn the seven roles of the president of the United States of America, so that they can list those roles and classify different actions of a president under those roles. The sequence below is an example of an advance organizer a teacher could use to facilitate attainment of those objectives. This advance organizer strategy engages students by asking them to recall prior knowledge relevant to their lives and the lesson. Furthermore, the Think Pair Share strategy can help students, individually and collectively, produce a substantial list of presidential actions in the past year. The students could then be guided in a collective discussion of where these actions fall under the various presidential roles. Having collaborated on this list, students have, in essence, prepared their brains to receive and make sense of the new information. 7 Think About Remember that Minute Earth video at the beginning of the section? Let’s try that again. View the video once more, keeping in mind what you have learned about advance organizers. Then answer the questions that follow. 1. What is an example of an advance organizer that a teacher could use to prepare students for this video lesson? 2. How will this organizer... • engage students? • help students connect to prior learning/existing cognitive structures? • discern what is important in the lesson? • organize content from the lesson? 1. How might a teacher reference this organizer during or after instruction? 2. Think about how you could implement an advance 8 Section 3 Benefits Why use advance organizers? To foster student engagement. Advance organizers establish a purpose and direction for students’ participation in the lesson while also serving to acquire their attention by virtue of the relevance, challenge, or intrigue of the lesson. To activate prior knowledge. When students have recalled prior, relevant information, their brains are better prepared to receive new information and connect that new information to an existing cognitive structure. To help students identify and organize important information. Advance organizers help students know what to look for as they participate in a lesson and provide a framework for organizing information (e.g., a problem/solution framework). To meet the needs of students. Students who are able to connect new knowledge to or situate new knowledge in their existing cognitive structures are better able to understand and retain new knowledge. Learn More About Advance Organizers Activities On Advance Organizers Advance Organizers in the Classroom Introduction to Advance Organizers Instructional Strategies 10 Section 4 Resources Advance Organizers in the Classroom: Teaching Strategies and Advantages. (2012). Retrieved from http://educationportal.com/academy/lesson/advanced-organizers-in-theclassroom-teaching-strategies-advantages.html Cues, Questions, and Advance Organizers | Researched-Based Strategies. (2005). Retrieved from http://www.netc.org/focus/ strategies/cues.php Dean, C. B., Hubbell, E. R., Pitler, H., & Stone, B. (2012). Classroom instruction that works. (2nd ed.). Denver: ASCD. McREL (2012). Classroom Instruction That Works [video file]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch? v=ARFKDv8aUik Middle School Biology Lesson Plan: Pond Water Safari [video file]. (2012). Retrieved from https:// www.teachingchannel.org/videos/middle-school-biologylesson Graphic Organizers Instructional Strategies First Impressions • How can I engage students with content? • How can I appeal to visual learners? • What strategies can I use to help students organize and retain new information? Objectives: Section 1 Definition and Purpose Students will be able to... 1. Define graphic organizers. 2. Identify general types of graphic organizers. 3. Describe how to use a graphic organizer called the Plus-MinusInteresting (PMI). 4. Recognize the benefits of using graphic organizers in the classroom. According to Instructional Strategies Online, graphic organizers “form a powerful visual picture of information and allow the mind 'to see' undiscovered patterns and relationships between ideas.” One group of specific organizers is known as Thinking Maps ®. Many schools are implementing these based on the work of David Hyerle. These eight (proprietary) maps are among hundreds of different types of graphic organizers available. What’s This? A graphic organizer... • is usually a one-page form with blank areas for students to fill in with related ideas and information. • may be referred to as a graphic representation, a visual representation, a mind map, or a pictograph. • may be in the form of a chart, a map, or a diagram. • engages learners with a combination of words and printed diagrams. • provides a visual aid to facilitate learning and instruction. • may be used in multiple content areas and across grade levels. 14 Take a Look Where can I find examples of graphic organizers? You can locate examples of sequential (hierarchy charts and timelines), cause and effect (T-charts, herringbone) and compare and contrast (Venn diagram) as well as many other graphic organizers from various locations around the web. Education Place and Enchanted Learning are two good places to start. How do you use graphic organizers? Because graphic organizers are flexible, you can use them before, during, and after instruction. Before Instruction - Using graphic organizers as an advance organizer, provides a structured preview of what is to be learned. During Instruction - Students can fill out a blank or partially completed graphic organizer while a teacher provides information or during a pause in a lecture to show what they have learned. Small teams of students may also work to complete a graphic organizer and solidify their understanding of a concept. After Instruction - Using a graphic organizer after instruction enables students to demonstrate their understanding and to state in concise terms what they have learned. Instructional Strategies 15 S PACE R ACE T IMELINE W RITING W EB O RGANIZER C HAD M ANIS D AILY T EACHING T OOLS . COM 16 Section 2 Real Life Examples E XAMPLE N ON E XAMPLE CHART How will graphic organizers look in my classroom? As mentioned before, graphic organizers are popular across content areas. The examples noted below show how particular organizers are used in specific disciplines; however, they can easily be used in every subject area. Social Studies: Spider Map Language Arts: Compare & Contrast Graphic Organizer Math: Venn Diagram Classroom Example of a Graphic Organizer The Plus-Minus-Interesting (PMI) chart was invented by Edward de Bono, who has repeated throughout his writing that critical and creative thinking can be taught. Reinforcing his belief, Common Core documents state that critical thinking is "a key performance outcome" that should be taught. The PMI writing/thinking protocol is intellectually useful in dozens of contexts and can be used for critical appraisal of any subject. It is particularly powerful for analyzing case studies and prewriting. Let’s think through how students in a high school English class might use a PMI chart as they prepare to write a "think piece" on the topic of drones that demonstrates both critical and creative thinking in fewer than 500 words. They are directed to use a PMI chart for their prewriting stage. Instructional Strategies PMI GRAPHIC ORGANIZER 18 The PMI Steps: Step 1: For two minutes in the plus column, students write about all of the possible positive aspects of drones. Step 2: For two minutes in the minus column, students write about all the possible negative aspects of drones. Step 3: For two minutes in the interesting column, students write about all the interesting aspects of drones, including implications and possible outcomes of using drones, whether positive, negative or uncertain. The six minutes that students spend working through the PMI protocol will help them arrive at topics that they can be passionate about exploring, such as drones as precursors of technologies that empower individuals. PMI GRAPHIC ORGANIZER 19 Think About Identify a critical concept in your content area, and then answer the questions that follow: 1. Would the PMI help students understand the topic or some aspect of the topic on a deeper level? 2. How will the PMI graphic organizer... • engage students? • help students connect to prior learning/existing cognitive structures? • discern what is important in the lesson? • organize their thinking? 3. Contemplate how you could implement the PMI in your classroom. Warning! Graphic organizers will not just teach themselves! According to Hall & Strangman (2002), “Without teacher instruction on how to use them, graphic organizers may not be effective learning tools. Graphic organizers can successfully improve learning when there is a substantive instructional context such as explicit instruction incorporating teacher modeling and independent practice with feedback.” 20 Section 3 Benefits Learn More About Graphic Organizers Graphic Organizers video Why use graphic organizers? To develop higher order thinking skills. Graphic organizers encourage the use of critical thinking skills, such as analyzing abstract concepts, while deepening comprehension and expanding connections among ideas. To aid in organization and recall of information. By organizing information visually, students are able to recall it more readily. Memory of vocabulary words and content knowledge are equally enhanced by the use of graphic organizers. To promote autonomy. Graphic organizers provide students with a means of breaking down procedures, such as the writing process, into achievable steps. This motivates students to manage their own learning. 22 Section 4 Resources Fountas, I., & Pinnell, G. (2001). Guiding readers and writers grades 3-6: Teaching comprehension, genre, and content literacy. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Hawk, P. P. (2006). Using graphic organizers were significantly beneficial to student achievement. Science Education, 70(1), 81-87. Gagnon, J., & Maccini, P. (2000). Best practices for teaching mathematics to secondary students with special needs: Implications from teacher perceptions and a review of the literature. Focus on Exceptional Children, 32(5), 1-22. Hill, J., & Flynn, K. (2006). Classroom instruction that works with English language learners. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Griffin, C. C., & Tulbert, B. L. (2006). The effect of graphic organizers on students’ comprehension and recall of expository text: A review of the research and implications for practice. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 11(1), 73-89. Hall, T., & Strangman, N. (2002). Graphic organizers. Wakefield, MA: National Center on Accessing the General Curriculum. Retrieved from http://aim.cast.org/learn/ historyarchive/ backgroundpapers/graphic_organizers#.UvfvV0JdVwo Howard, P., & Ellis, E. (2005). Summary of major graphic organizer research findings. Retrieved from http:// www.hoover.k12.al.us/hcsnet/rfbms/makessense7.4/ donotopenfolder/implmnt/dontopen/msstrats/stuf/ GOMatrix.pdf Paul, Walter. (2001). How to Study in College. Retrieved from http://lsc.cornell.edu/LSC_Resources/cornellsystem.pdf Hyerle, D. (1996). Thinking maps: Seeing is understanding. Educational Leadership, 53(4), 85-89. Resources Hyerle, D. (2000). Thinking maps: Visual tools for activating habits of mind. In A. L. Costa & B. O. Kallick (Eds.), Activating and Engaging Habits of Mind (pp. 46-58). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Shankland, L. (2010). A plan for success: Using thinking maps to improve student learning. SEDL Letter, 22(1), 3-4. Lott, G. W. (1983). The effect of inquiry teaching and advanced organizers upon student outcomes in science education. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 20(5), 437-451. Togo, D. F. (2002). Topical sequence of questions and advance organizers impacting on students’ examination performance. Accounting Education, 11(3), 203-216. Marzano, R. J., Pickering, D. J., & Pollock, J. E. (2001). Classroom instruction that works: Research-based strategies for increasing student achievement. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Robinson, D. H., & Kiewra, K. A. (1995). Visual argument: Graphic organizers are superior to outlines in improving learning from text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87(3), 455-467. Stone, C. L. (1983). A meta-analysis of advanced organizer studies. Journal of Experimental Education, 51(4), 194-99. Walberg, H. J. (1999). Productive teaching. In H. C. Waxman & H. J. Walberg (Eds.). New directions for teaching practice and research (pp. 75-104). Berkeley, CA: McCutchen Publishing Corporation. Williams, S. C. (2002). Find Your Way With Thinking Maps. Teaching for Excellence, 21(8), 1-2 Willis, S., & Ellis, E. (2010). The theoretical and empirical basis for graphic organizer instruction. Northport, AL: Makes Sense Strategies. Retrieved from http://www.graphicorganizers.com/ images/stories/pdf/GO_Emperical_Theoretical_Basis.pdf 24 Subject Specific Instructional Strategies Career & Technical Education Section 1 Career & Technical Education Advance Organizers The Career and Technical Education subject matter is threaded throughout the common core content. As students develop fundamental skills in language arts, mathematics, social studies, and science, a variety of forms of text, technology, and media are introduced as well. To this end, CTE curriculum often includes advance organizers that are embedded in computer-based technology and multimedia software tools. The advance organizers should serve as a model for helping students organize information by connecting it to a larger cognitive structure that reflects the organization of the discipline (Kirkman & Shaw, 1997, 3). CTE computer based technology integration ideas include: Bubbl.us Using Bubbl.us, students develop communication, brainstorming, and critical thinking skills. In the example below, you can see how students in a finance course were assigned a central idea based on the topic which was to be taught the following day. The students recorded their ideas in color-coded bubbles, saved the material, and printed a copy of the work to be shared during the opening activity the following day. This strategy provided an excellent way to measure the students’ current knowledge of the topic prior to instruction. It also prepared students by previewing important terminology that would be addressed during class the next day, providing students with a basic understanding of the terms and open dialogue. Tools4Students Many schools today have incorporated iPad carts that can be used in the classroom. The Tools4Students iPad app offers 25 graphic organizers that can be used, emailed, and shared with classmates. Create a Word Cloud If you are trying to differentiate your instruction to meet the needs of the visual learners in class, a simple word cloud generator such as Wordle puts important information in a fun format for students to view. Tagxedo, a similar site, even allows you to transform the word cloud into a shape. The VocabGrabber tool, which enables you to input and analyze a text and generate a vocabulary list from it, provides assistance if you are trying to develop your students’ academic language. In the example provided here, text was taken from the Revised Blooms Taxonomy available on the DPI website and input into the VocabGrabber. Vocabulary words were generated and organized by color and size to depict the number of times the words were used. Student-generated Cornell Notes Another method of engaging students during direct instruction is to have them generate notes using the Cornell method. The method, created by Cornell Professor Walter Pauk, divides a standard notebook paper into sections that can be used for organizing and formatting notes. Students are further required to complete three follow up activities: revising, generating questions, and writing a brief summary, which aids students in identifying important information. Additional Resources for Web Based Advance and Graphic Organizers KWL Chart Cause and Effect Diagram Cycle Organizer T-Chart Credits Development of the ISLES modules was supported financially by the Teacher Quality Partnership grant program of the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Innovation and Improvement. Images used with permission. ©2014 East Carolina University Creation, development, and editing were provided by the following individuals: Adu-Gyamfi, Kwaku; Barker, Renea; Berry, Crisianee; Brown, Cindi; Eissing, Jennifer; Finley, Todd; Flinchbaugh, Michael; Garner, Kurt; Guidry, Allen; Harris, Julie; Hodge, Elizabeth; Hutchinson, Ashley; Jenkins, Kristen; Kester, Diane; Knight, Liza; Lewis, Greg; Liu, Yan; Noles, Stephanie; Nunns, Kristen; Passell, Robert; Pearce, Susan; Perkins, Ariel; Phillips, Joy; Phillips-Wagoner, Ashleigh; Ross, Chad; Sawyer, Eric; Smith, Lisa; Smith, Jedediah; Steadman, Shari; Swope, John; Thompson, Tony; Todd, Clinton; Ware, Autumn; Williams, Scott; Zipf, Karen.