The Market for Substitute Classroom Teachers in

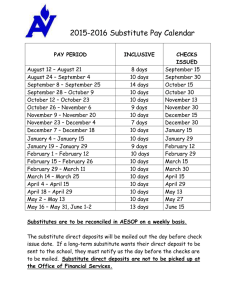

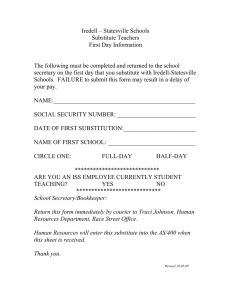

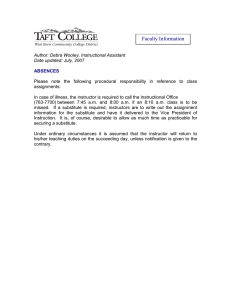

advertisement