Draft for discussion – not to be quoted

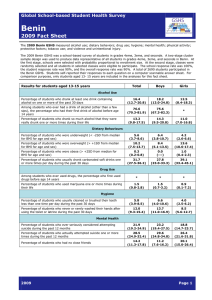

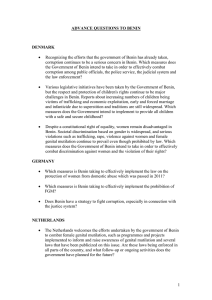

advertisement